È difficile immaginare un ambiente più adatto del Trinity Centre di Bristol per fare esperienza dei sound system: una sala dal soffitto alto nel cuore di una chiesa del XIX secolo, con angoli bui e uno spazio ampio per ballare. Basta venire a uno degli eventi di Teachings In Dub, quando l’impianto è impilato fino al soffitto e distribuito in modo da dividere la stanza, per presenziare a un’esperienza altamente immersiva, guidata da bassi così potenti da riorganizzare ogni fibra del tuo essere. Capitanato dalle figure più celebri della scena Dubkasm, la serata è il classico dance comunitario che riunisce un pubblico variegato sotto le sonorità dub, roots e steppas più autentiche. Teachins In Dub è un’istituzione per la scena musicale locale: nata sulle solide fondamenta gettare dalla prima ondata di migranti caraibici che si stabilirono in città, continua a riproporre quella storia d’amore intrinseca tra Bristol e la cultura dei sound system.

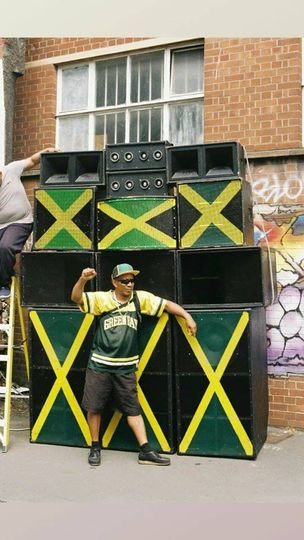

Camminando lungo City Road a St Pauls, a 15 minuti a piedi dal Trinity Centre, c’è un grande murale che occupa per intero il lato di una villetta a schiera. Si intitola Migration, ed è un omaggio alla “Generazione Windrush”: quelle prime 492 persone, tra uomini, donne e bambini che su invito reale, nel 1948, attraversarono l’Atlantico partendo dalle Indie Occidentali per ricostruire la Gran Bretagna dopo la Seconda Guerra Mondiale. Ebbe inizio così un forte movimento diasporico, con tutto il ricco bagaglio della cultura caraibica, che ebbe come centro proprio il quartiere di St Pauls. Si stima che alla fine degli anni Cinquanta circa 50mila migranti ogni anno finissero per stabilirsi in Gran Bretagna, attratte dalla promessa di lavoro e dall’idea di una vita migliore per le loro famiglie. Ma come nella più deprimente continuazione dello sfruttamento notoriamente perpetuato dall’epoca coloniale, quel che aspettava queste migliaia di persone era ancora disuguaglianza e segregazione. Cosicché, queste comunità diasporiche, non poterono che edificare i propri mondi per esprimere sé stessi e la propria cultura.

«Non c’erano grandi club, ma se ne sentiva un enorme bisogno» racconta Jah Vego a Lloyd Bradley nel fondamentale Bass Culture, «ed è per questo che qui il business dei sound system è decollato come ha fatto. Penso che le persone che arrivarono in Inghilterra fossero più ricettive alla musica dance giamaicana di quanto lo fossero persino in Giamaica… ogni evento era molto atteso, quasi che fosse una parte di Giamaica a cui ancora si poteva presenziare».

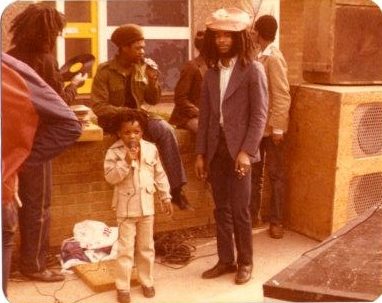

Con solo un paio di sound-system presenti a Londra negli anni Cinquanta, la cultura si diffuse velocemente in altre città del paese con consistenti popolazioni giamaicane. Esclusa dai club principali a causa del clima di tensione razziale, la comunità diasporica iniziò a ritrovarsi in sale comunitarie, palestre o case e a trasformarle in club improvvisati per la notte. Le feste nelle case – conosciute anche come shebeens o blues dances – potevano continuare per tutto il weekend in aree che la polizia spesso evitava.

A Bristol, il Bamboo Club aprì a St Pauls nel 1966: fu il primo luogo ad accogliere la nascente cultura dei sound system in città. Pionieri come Tarzan The High Priest (nonno della futura leggenda di Bristol, Tricky), Count Ajax e Honey Bee fecero i loro primi passi nell’organizzare dance comunitarie, e così numerosissime blues dances sorsero attorno a St Paul’s e soprattutto nel vicino quartiere di Easton. A partire da questo inizio tutto sommato modesto, negli anni Settanta l’entità del fenomeno crebbe a dismisura, specialmente grazie a locali come la Mayfair Suite, il Mill Youth Centre e l’Inkerman – e anche dopo che il celebre Bamboo Club bruciò nel 1977, c’erano già spazi più grandi come il Trinity e il Malcolm X Centre a ospitare le dance comunitarie.

La prima ondata della Generazione Windrush portò con sé mento e ska, che si evolsero naturalmente in rocksteady, reggae e dub.

La prima ondata della Generazione Windrush portò con sé mento e ska, che si evolsero naturalmente in rocksteady, reggae e dub, mentre questi stili prendevano piede in Giamaica. La stessa gioventù disillusa che, negli stessi anni, contribuì all’esplosione del punk in Gran Bretagna trovò diverse affinità con quella che era l’idea ribelle insita nel reggae, quella di una musica per una comunità emarginata.

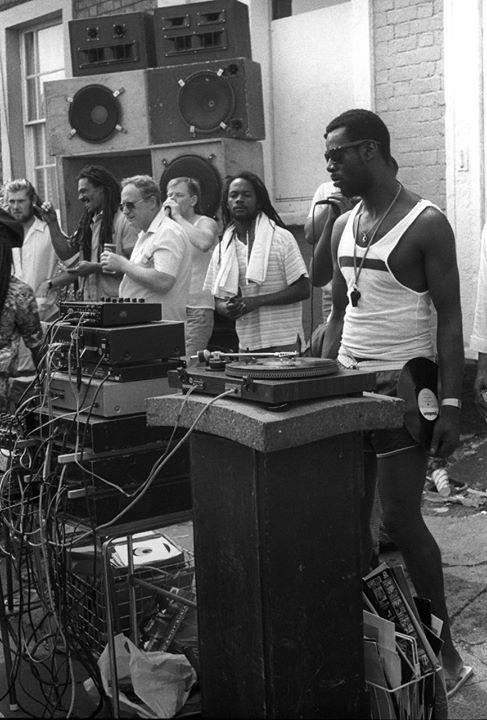

L’incontro tra reggae, dub e punk alimentò risultati musicali unici in diverse parti del Regno Unito, ma fu particolarmente potente a Bristol, dove band come The Pop Group assorbirono le influenze delle leggendarie house blues – come Ajax Blues – e le canalizzarono in interpretazioni sperimentali del punk. Nel frattempo, sound system come Enterprise Imperial Hi-Fi e Froggy’s Excalibur salirono alla ribalta negli anni Settanta e Ottanta.

Quasi come se Bristol stessa avesse un istinto per i crossover culturali, in città seguitarono a emergere sound system e band. Sebbene l’approccio tradizionale alla musica roots sia perdurato, negli anni Ottanta si verificarono alcune rivoluzioni significative, in particolare l’inizio dell’hip-hop a New York e il seguente arrivo della cultura dei B-Boy a Bristol. I The Wild Bunch emersero come leader della scena, prendendo spunto dai loro predecessori nei sound system e mescolando tra loro funk, soul, hip-hop, dub, punk ed electro. Milo Johnson, Nellee Hooper, Daddy G, Mushroom e 3D portarono influenze diverse nelle sonorità allora canoniche, rompendo gli schemi e spingendo la colonna sonora dei party di Bristol verso nuovi orizzonti – assieme ad altre crew come 2Bad, FBI Crew, Smith & Mighty e Fresh 4. Partecipando a sound clashes in tutta la città e con gruppi come Soul II Soul a Londra, grazie allo spirito competitivo e agli sforzi collettivi che attingevano dalla cultura sound system, la scena intraprese direzioni inedite.

Durante questo momento di cambiamenti, ci fu però una costante per la cultura sound system di Bristol: il Carnevale di St Pauls. Fondato nel 1968, l’evento rispecchiava manifestazioni simili a Notting Hill a Londra, Chapeltown a Leeds e Handsworth a Birmingham, in cui le comunità caraibiche celebravano e condividevano la propria cultura nell’arco di un’intera giornata e un’intera notte di festeggiamenti, con i sound system che inondavano le strade di musica. Nel corso degli anni, il Carnevale di St Pauls è stato un terreno di prova per le crew emergenti della città: basta ricordare quell’evento notorio in cui Froggy propose ai The Wild Bunch di suonare sul suo sistema Excalibur all’inizio degli anni Ottanta. Ovviamente, simili eventi hanno anche portato la cultura dei sound system a migliaia di persone, sia della città che da fuori, esponendo così nuovi devoti al fascino misterioso dei bassi pulsanti nella loro forma più materica.

Sonorità spaziose, cupe e ricche di bassi, con quella tipica inclinazione di Bristol a fondere stili improbabili in qualcosa di emozionante e imprevedibile.

Così, se negli anni Ottanta la cultura dei sound system era principalmente un’impresa di spirito locale, il decennio successivo spinse alcuni artisti verso una più ampia notorietà. I Fresh 4 raggiunsero la Top 10 delle classifiche britanniche con la loro cover di Wishing On A Star dei Rose Royce, mentre la frammentazione dei The Wild Bunch diede vita ai Massive Attack. Questi suoni DIY stranamente soul presero piede: vista l’entità del fenomeno, i critici coniarono dunque la dubbia etichetta di “Bristol sound”, assieme a quella ancor più dubbia del “trip hop” nella metà degli anni Novanta. Quelle sonorità che allora erano considerate controculturali, promosse da artisti come Tricky, nascevano radicate nei princìpi tecnici dei sound system: sonorità spaziose, cupe e ricche di bassi, con quella tipica inclinazione di Bristol a fondere stili improbabili in qualcosa di emozionante e imprevedibile.

Negli stessi anni, un altro genere si affacciava sulla scena. Il radicamento ormai consolidato della cultura dei sound system in UK giocò un ruolo centrale nello sviluppo della techno e dell’acid house britannica, specialmente alla fine degli anni Ottanta, quando DJ e produttori cominciarono a prediligere le accelerazioni dei break hip-hop, e contribuendo così alla nascita il breakbeat hardcore nei primi anni Novanta. Era l’alba della jungle. Tutte sonorità e generi che riconoscono l’eredità dei sound system poiché su questi sono fondati, con batterie scheletriche e bassi schiaccianti: proprio come la dub. Cosicché a Bristol, i membri dei Fresh 4, Krust e Suv, si unirono a DJ Die e Roni Size per formare Full Cycle, dando vita a un’importante e anticonformista diramazione dell’esplosione irrefrenabile della jungle. Nel frattempo, il fratello di Krust, Flynn (anch’egli dei Fresh 4), si unì a Flora per creare una propria particolare variante del breakbeat, mentre Smith & Mighty si concentrarono sul progetto More Rockers, per far valere il peso della loro esperienza nella scena ormai in piena espansione.

Jungle e drum & bass divennero una presenza permanente nel panorama musicale di Bristol, trovando infine spazio anche nell’ambiente musicale più tradizionalista del Carnevale, accanto ai sound system puristi come Jah Lokko e Negus Melody, mentre si affermavano nei club e nei festival di tutto il Paese. Tra l’inizio e la metà degli anni Duemila arrivò ancora un’altra variante, un’altra propaggine, costruita su misura per i sound system e intrisa come una spugna della storia sonora iniziata dalla diaspora caraibica, e importata e assimilata nel Regno Unito. Pinch fu tra i primi a Bristol a raccogliere l’eredità della dubstep, organizzando le serate Context in tempi per niente sospetti – riecheggiando le stesse dinamiche peculiari, d’istinto per i fenomeni crossculturali, per cui la jungle assunse un tocco distintamente bristoliano quando arrivò in città.

In una stanza potevi vedere Aba Shanti-I predicare un classico sermone dub su un sound travolgente, mentre al piano superiore Pinch, Peverelist, Jakes e Joker traghettavano la dubstep in pertugi sonori sconosciuti e selvaggi.

Con l’affermarsi della dubstep di Bristol attraverso una rete di artisti ed etichette, Pinch passò da Context a Subloaded, e si impegnò a collaborare con gli eventi Teachings In Dub di Dubkasm per mettere in evidenza la sinergia tra la musica roots e questa nuova ondata di sonorità sound system. In una stanza potevi vedere Aba Shanti-I predicare un classico sermone dub su un sound travolgente, mentre al piano superiore Pinch, Peverelist, Jakes e Joker traghettavano la dubstep in pertugi sonori sconosciuti e selvaggi.

Seppur oggi i generi nati e formatisi nell’eredità dei sound system si siano ulteriormente frammentati e diversificati – tanto in Bristol quanto altrove –, e alcuni loro sviluppi si siano allontanati dalla natura prettamente fisica e materica della scena e dalle radici geografiche, si vede una chiara discendenza di stampo “bristoliano” in diversi artisti, etichette e collettivi. C’è Young Echo, che riunisce un gruppo di artisti estremamente eclettici e alimentati da un’etica punk DIY e dall’influenza dominante della dub – specialmente nel pioniere intransigente Ossia e nelle sue infuocate performance dal vivo, con un tocco di industrial. Firmly Rooted ha invece riversato la propria energia nella costruzione di un sound system fedele alla tradizione, pur dando spazio ai nuovi sviluppi nella dub e nelle più ampie sfumature della musica bass. C’è poi il collettivo Bristol NormCore, che mette i principi del sound system al centro dei loro eventi, dando la stessa importanza al sistema utilizzato quanto ai DJ sperimentali e agli artisti invitati, sia che si tratti di Sinai Sound o Qualitex a fornire l’impianto.

Come ogni storia e cultura di ogni città, quella dei sound system di Bristol è una narrazione in continua evoluzione. Una narrazione non lineare, che porta però sempre con sé un profondo rispetto per i pionieri del passato e per quel principio di comunità su cui si è sempre fondata la scena, seguitando a mixare forme e generi musicali, quasi obbligandoli a far nascere nuovi stili. Come intona Solo Banton nel classico moderno di Dubkasm, Tell The World, «drum & bass, dubstep e persino hip-hop prendono tutte le loro radici dal sound-system». Se mai una frase potesse riassumere lo spirito dell’approccio unico di Bristol alla cultura sound system, sarebbe di certo questa. Stili distinti e autonomi con radici comuni.

Di questa eredità, Hyperlocal Festival ospiterà il sound system di Bass Unity, con DJ set di Big D (Jah Lokko), Odd Shy Gyu e ROse Again (Bristol Normcore), Ossia (Young Echo) e un b2b tra Pinch e Yushh. Il tutto sarà preceduto da una conversazione moderata dal critico musicale Shawn Reynaldo con Pinch e Big D.

It’s hard to imagine a more fitting setting than Bristol’s Trinity Centre for a sound system experience — a high-ceilinged, functional room in the heart of a 19th-century church with dark corners and ample room to dance. When a Teachings In Dub event is in session, the rig is stacked high, usually split across the room to create a truly immersive experience led by low-end powerful enough to rearrange every fibre of your being. Helmed by scene leaders Dubkasm, it’s the quintessential community dance bringing together a broad crowd under the banner of authentic dub, roots and steppas in a continuation of Bristol’s intrinsic love affair with sound system culture. It’s an institution for the local music scene built on firm foundations laid by the first wave of West Indian migrants to settle in the city.

If you walk down City Road in St Paul’s, a 15-minute walk from Trinity Centre, the entire side of one townhouse is covered in a mural dubbed ‘Migration’ paying tribute to the Windrush Generation. It’s a loving recognition of the 492 men, women and children who first crossed the Atlantic from the West Indies in 1948 under royal invitation to help rebuild Britain after the Second World War. The majority of those who arrived in Bristol settled in St Paul’s, bringing with them their Caribbean culture, not least the food and the music.

By the late 1950s, every year as many as 50,000 migrants were settling in Britain from the West Indies, rapidly forming diasporic communities lured by the promise of employment and a better life for their families. In a depressing continuation of Britain’s exploitative colonial legacy, it was inequality and segregation that awaited them, and so these communities created their own self-contained worlds in which to express themselves and their culture.

“There weren’t no big clubs, but the need for them was big,” Jah Vego told Lloyd Bradley in the seminal book Bass Culture, “which is why the sound-system business took off here as it did. I think people that had come to England was more receptive to a Jamaica-style dance than even they had been in Jamaica… here they look forward to them as one of the only parts of Jamaica they can still partake in.”

From just a couple of sound systems in London in the 1950s, the culture soon spread across the country to other towns and cities with significant Jamaican populations. Barred from high street clubs due to the simmering stew of racial tension, the new Black population in Britain instead found community halls, gymnasiums or houses to turn into makeshift clubs for the night. The houses — also known as shebeens or blues dances — could rage on all weekend in areas the police would often avoid.

In Bristol, The Bamboo Club opened in St Paul’s in 1966 as a venue that catered to the earliest sound system culture in the city. Pioneers such as Tarzan The High Priest (grandfather to future Bristol legend Tricky), Count Ajax and Honey Bee made their first steps into hosting dances, and the blues dances sprung up around St Paul’s and the neighbouring Easton district. What started modestly grew in strength and stature into the 1970s across venues like the Mayfair Suite, The Mill Youth Centre and The Inkerman, and even after The Bamboo Club burned down in 1977, there were already bigger spaces like Trinity and the Malcolm X Centre to house community dances.

The first wave of the Windrush Generation brought mento and ska with them, naturally evolving into rocksteady, reggae and dub as the styles took hold back in Jamaica. In tandem, when punk broke across Britain in the late 70s, it was spearheaded by a disaffected youth who found kinship with the de facto rebel status of reggae as the music of an outcast community. The crossover between reggae, dub and punk fuelled unique musical outcomes in different parts of the UK, but it was especially potent in Bristol as bands like The Pop Group took the influence they were soaking up at legendary blues’ like Ajax and funnelled it into their experimental twist on punk. Meanwhile, soundsystems like Enterprise Imperial Hi-Fi and Froggy’s Excalibur rose to prominence through the 70s and 80s.

Bristol’s instinct for cultural crossovers manifested in the sound systems as well as the city’s bands. While the traditional approach to roots music has endured through the ages, in the 80s there were great revolutions taking place not least thanks to the emergence of hip-hop in New York. As B-Boy culture made its way to Bristol, The Wild Bunch emerged as scene leaders taking their cues from their soundsystem forebears while joining the dots between funk, soul, hip-hop, dub, punk and electro. Milo Johnson, Nellee Hooper, Daddy G, Mushroom and 3D brought diverse influences into their sound, shattering the mould and pushing Bristol’s party soundtrack in new directions alongside other crews such as 2Bad, FBI Crew, Smith & Mighty and Fresh 4. Taking part in sound clashes around the city and with the likes of Soul II Soul in London, their competitive spirit and collective endeavours drew from sound system culture and took it entirely elsewhere.

Throughout this era of change, one constant remained for Bristol’s soundsystem culture – St Paul’s Carnival. Founded in 1968, the event mirrored similar events in Notting Hill in London, Chapeltown in Leeds and Handsworth in Birmingham as the West Indian communities sought to celebrate and share their culture in a glorious day and night of festivities, soundtracked by sound systems filling the streets with music. Throughout the years St Paul’s Carnival has been a proving ground for the city’s hopeful crews, with Froggy infamously giving the Wild Bunch one of their first breaks on his Excalibur system in the early 80s. The annual event also presented sound system culture to thousands from the city and beyond, exposing new devotees to the mysterious allure of pulsing sub-bass in its most physical form.

If sound system culture was primarily a locally spirited endeavour in the 80s, as the decade turned, it pushed certain artists to wider notoriety. Fresh 4 hit the Top 10 of the UK charts with their cover of Rose Royce’s ‘Wishing On A Star’ while the splintering of The Wild Bunch gave rise to Massive Attack. These strangely soulful DIY sounds caught on, helping pundits coin the dubious ‘Bristol sound’ tag ahead of the even more dubious ‘trip hop’ phenomenon of the mid-90s. The misfit sounds pushed by the likes of Tricky were rooted in sound system principles — spacious, moody and bass-heavy, with the unique Bristol affinity for meshing unlikely styles into something thrillingly new and unpredictable.

At the same time, another urgent form of sound system music was rushing into existence. The UK’s bedded-in soundsystem culture had a big part to play in the development of UK techno and acid house in the late 80s, not least as DJs and producers sped up hip-hop breaks until breakbeat hardcore came through in the early 90s and mutated into jungle. This was music absolutely founded on the legacy of the sound system, with skeletal drums and crushing bass like any dub. In Bristol, the former Fresh 4 members Krust and Suv linked up with DJ Die and Roni Size to form Full Cycle and a vital, non-conformist splinter of the jungle explosion was born. Meanwhile Krust’s brother Flynn (also of Fresh 4) linked up with Flora to make their own distinctive strain of breakbeat, while Smith & Mighty pivoted to the More Rockers project to bring their own weight of experience to the booming scene.

Jungle and drum & bass became a permanent staple of Bristol’s musical makeup, eventually finding its way into the more traditionally-minded musical landscape of the Carnival alongside purist systems like Jah Lokko and Negus Melody even as it took hold in clubs and festivals up and down the country. It was followed up in the early to mid-00s by the arrival of another sound custom-built for sound systems, steeped in the heritage of the UK’s imported and assimilated music culture. Pinch was among the first in Bristol to pick up on dubstep, putting on Context nights well ahead of the curve and echoing the way jungle took on a distinct Bristolian twist when it hit the city.

As the Bristol dubstep scene in Bristol grew in a network of artists and labels, Pinch progressed from Context to Subloaded and made a point of linking up with Dubkasm’s Teachings In Dub events to highlight the synergy between roots music and this new wave of soundsystem sonics. In one room you could see Aba Shanti-I delivering a classic dub sermon on an ear-shattering sound while upstairs Pinch, Peverelist, Jakes and Joker were taking dubstep in wild new directions.

In the post-dubstep era, music has splintered and fragmented in many different ways in Bristol and beyond. Many developments have edged away from the physical, geographically rooted community nature of former scenes and sounds, but some artists, labels and collectives display a clear lineage from Bristol’s earlier soundsystem eras. Young Echo gathers together a wildly eclectic group of artists fuelled in equal parts by a DIY punk ethic and the overbearing influence of dub, not least in uncompromising trailblazer Ossia and his incendiary, industrial-tinged live performances. Firmly Rooted have poured their energy into building a sound system which stays true to the tradition while also platforming new developments in dub and broader strains of bass music. Meanwhile, Bristol NormCore put sound system principles at the forefront of their events, with the system they use getting equal billing alongside the distinctly experimental DJs and live acts they book, whether it’s Sinai Sound or Qualitex providing the rig.

As in all cities and cultures, Bristol’s sound system story is an ever-evolving, non-linear narrative which carries deep reverence for the pioneers of the past and the message of community, folding existing musical forms into each other until wild new styles emerge. As Solo Banton intones on Dubkasm’s modern classic ‘Tell The World’, “drum & bass, dubstep and even hip-hop all take their roots from the sound system.”

If ever one phrase summed up the spirit of Bristol’s unique approach to sound system culture, this would be it — distinct styles with shared roots, heading in exciting and unpredictable new directions.

Drawing from this legacy, the Hyperlocal Festival will host the Bass Unity sound system, featuring DJ sets by Big D (Jah Lokko), Odd Shy Guy and Rose Again (Bristol Normcore), Ossia (Young Echo), and a b2b between Pinch and Yushh. The event will be preceded by a conversation moderated by music critic Shawn Reynaldo with Pinch and Big D.