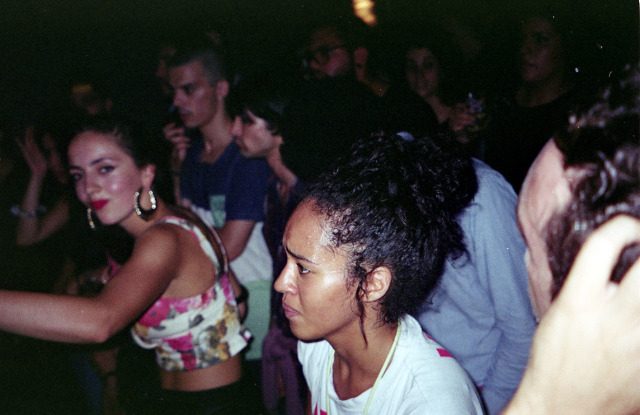

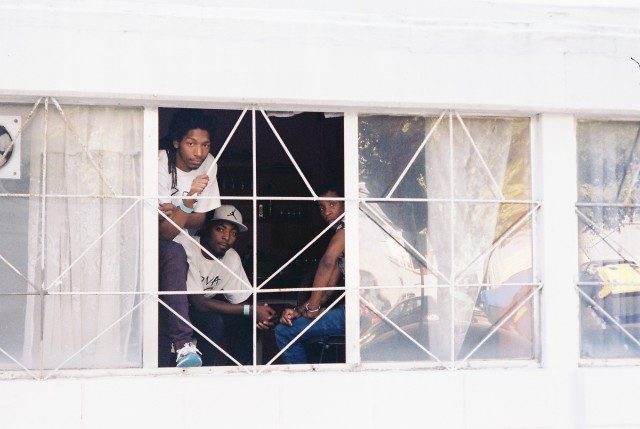

Non sono mai stata tra la folla di Noite Príncipe, e nemmeno ho mai frequentato le periferie di Lisbona. Ma avrei desiderato esserci quando la leggendaria Príncipe Discos divenne una presenza costante al Musicbox, un pilastro della vita notturna lisbonese, e assistere a quelli che furono gli esordi della batida, conformazioni sonore mai sentite prima create con software craccati su computer a basso costo. Guardo alle foto di scattate da Marta Pina, una delle fotografe di Prìncipe: un pranzo comunitario domenicale nei giardini di un complesso residenziale in periferia; i grattacieli suburbani costantemente sullo sfondo; un pubblico sudato e reverenziale che danza, esposto per la prima volta alla batida; camere da letto oscurate da tende tese, con piccole folle che attorniano schermi di vecchi computer su cui si intravede FL Studio.

Non ero a Lisbona, ma ho potuto sperimentare cosa fosse la batida qualche anno dopo che quelle foto vennero scattate. Un vortice di ritmi percussivi e sinistri, un incantesimo che obbliga le membra a scatenarsi: questo era il dj set di Vanyfox, figura di spicco nella scena più giovane della batida nonché uno dei talenti di Moonshine, acclamato collettivo di Montreal focalizzato sulla club culture africana e diasporica che funge da ponte sonoro tra il retaggio musicale diasporico e le diverse città in cui si esibisce. Fu in quella serata al Dock B di Pantin, in una notte invernale parigina, che conobbi per la prima volta la batida.

La batida nasce come termine ombrello per raccogliere la moltitudine di ibridi sonori che emergono costantemente dall’incontro tra gli stili regionali dei paesi africani lusofoni e la musica elettronica europea.

Secondo Daviaa, produttore anglo-portoghese e fondatore del programma radiofonico Na Tchada su Reprezent Radio, Vanyfox appartiene a una lunga lista di artisti emergenti e talentuosi che stanno spostando i confini della batida verso lidi inediti. Ci sono DJ Tyson, che fa parte di quelli che rallentano i consueti 140 bpm del genere; Danifox e Lycox, che aggiungono voci e vocalizzi al beat; Dariiofox, il più vicino alle origini sonore della batida, influenzato dal fratello DJ Nervoso; Nuno Beats e DJ Narciso, membri della sperimentale RS Produções, maestri di tensione e rilasci, e così via. La maggior parte di loro è sotto Príncipe Discos, l’etichetta lisbonese che promuove la musica dance contemporanea della città, delle sue periferie e dei suoi ghetti, riconosciuta come uno dei progetti più rilevanti sulla piazza globale. D’altronde, la firma di Príncipe è proprio la batida, che nasce come termine ombrello per raccogliere la moltitudine di ibridi sonori che emergono costantemente dall’incontro tra gli stili regionali dei paesi africani lusofoni e la musica elettronica europea.

Profondamente radicata nelle periferie di Lisbona, l’identità sonora e multiforme della batida iniziò a emergere nel fervore della musica elettronica dei primi anni 2000. Si trattò all’inizio di un mix artigianale di kuduro angolano e altri stili africani portati in Portogallo dalla diaspora lusofona, e mescolati con le nuove possibilità offerte dalla democratizzazione dei primi software di audio digitale. Si potrebbe dire che tutto iniziò con DJs Di Guetto Vol. 1, il primo album lanciato nel 2006 da un gruppo che includeva DJ Nervoso, DJ Marfox e DJ Firmeza – tutti residenti nei quartieri periferici di Lisbona: da Quinta do Mocho, ora considerata la culla della scena, a Quinta da Vitória, Baixa da Banheira, Queluz Massamá e Barcarena. La compilation, disponibile per il download gratuito online, si diffuse rapidamente, e non ci volle molto prima che altri paesi europei se ne accorgessero, cominciando a portare la batida fuori dalla capitale portoghese.

La compilation venne strategicamente rilasciata a settembre, all’inizio dell’anno scolastico. La maggior parte dei pionieri della batida era infatti ancora a scuola quando gettarono le basi del genere, smanettando su versioni craccate di FL Studio. Nonostante fossero ancora merce rara, nei primi anni 2000 i computer iniziarono lentamente a diventare più disponibili, a scuola o a casa di amici, e con l’entusiasmo scaturito con i primi software di produzione audio i DJs Di Guetto lavorarono sulle influenze sonore a cui erano stati esposti dalle comunità afrodiscendenti dei quartieri periferici di Lisbona. Comunità che includevano immigrati di prima, seconda e terza generazione provenienti da Angola, Mozambico, Capo Verde, Guinea-Bissau e São Tomé e Príncipe – tutti paesi che condividono una storia coloniale con il Portogallo. È da questi luoghi e dai loro contesti culturali che bisogna cominciare se si vuole comprendere il ruolo della batida oggi, in particolare da uno dei suoi riferimenti principali: il Kuduro.

Tra la fine degli anni Ottanta e l’inizio degli anni Novanta, l’Angola stava attraversando la guerra civile che seguì alla sua indipendenza dal Portogallo nel 1974. Come ricordato dal ricercatore Gerth Sheridan, lo scambio che nacque dai diversi viaggi della classe media angolana in Portogallo e nel resto dell’Europa durante le tregue introdusse i giovani di Luanda a una nuova gamma di registrazioni importate – trovate nei mercati di strada, nei club e nei rave – e strumenti musicali. Ben presto, le scene emergenti di house e techno che stavano attecchendo in Europa influenzarono i club angolani, dove i DJ iniziarono a incorporare questi generi accanto al pop americano e agli stili regionali come kizomba e zouk.

Il kuduro, che si traduce in “vita dura” – o più specificatamente “culo duro” – emerge dalla mescola di questi generi e diventa presto popolare durante gli ultimi anni della guerra civile angolana. Basta leggere i testi per comprendere come il kuduro fosse una valvola di sfogo tanto quanto l’esito di una speranza rivolta al futuro del paese, una sorta di collante che contribuiva a rafforzare l’identità nazionale – Marissa J. Moorman, studiosa di storia angolana e dei media africani Marissa J. Moorman, osserva a tal riguardo come il kuduro sia stato spesso cooptato dai governi e dai funzionari militari per specifici obiettivi politici. Da qui, il genere raggiunse una popolarità trasversale quando i lavoratori della classe operaia di Luanda crearono la loro versione: più veloce, più dura e con testi che articolavano l’esperienza di vivere nei musseques, le baraccopoli di Luanda.

Il kuduro è stato il principale genere a contribuire alla batida, ma non l’unico. Assieme alle influenze elettroniche europee, il kuduro uptempo si fonde con la tarraxinha angolana, il funaná capoverdiano e lo zouk: tutti stili musicali radicati in diverse regioni africane lusofone, che coincidono con la diaspora afrodiscendente a Lisbona. Se la tendenza iniziale della batida è quella che vede il kuduro nascere a Luanda sotto l’influenza europea, mano a mano il patrimonio culturale e sonoro della diaspora diventa per intero centrale: le configurazioni diasporiche e la loro geografia diventano intrinseche all’identità del genere.

Centrale nello sviluppo internazionale della batida fu la nascita di Príncipe Discos, fondata da Márcio Matos, José Moura, Nelson Gomes e André Ferreira. L’etichetta fu lanciata nel 2011 con il debutto di DJ Marfox, Eu Sei Quem Sou, che definì l’identità sonora e la direzione di Príncipe. Quello stesso anno, Marfox divenne un collegamento chiave tra l’etichetta e i quartieri periferici dove la batida stava guadagnando terreno, reclutando le voci emergenti più talentuose della scena. Tra i primi reclutati c’era DJ Nigga Fox, la cui prima release O Meu Estilo, rappresentò secondo Matos una svolta cruciale per l’etichetta. Successivamente Nídia, DJ Firmeza e DJ Nervoso si unirono alla scena. Entro la metà degli anni 2010, i DJ di Príncipe si esibivano al Sonar, al Roskilde e al MoMA di New York.

«Clacson, allarmi antincendio, suoni percussivi e chiacchiere indistinguibili in portoghese, creolo capoverdiano e slang angolano»: alla stregua di un archivio, come lo descrive il sociologo Otávio Raposo, l’acustica atmosferica del quartiere campionata nei brani della batida svolge un ruolo fondamentale.

Nonostante tutto, l’identità della scena rimane ben radicata alle sue origini geografiche e culturali. «Clacson, allarmi antincendio, suoni percussivi e chiacchiere indistinguibili in portoghese, creolo capoverdiano e slang angolano»: alla stregua di un archivio, come lo descrive il sociologo Otávio Raposo, l’acustica atmosferica del quartiere campionata nei brani della batida svolge un ruolo fondamentale. Questo «strato di informazione sonora», ha, secondo lo studioso, il potere «di inscrivere storie silenziate» e «corpi sistematicamente esclusi» nella narrazione e nella sfera pubblica del Portogallo. Come DJ Marfox ha detto una volta a Raposo, «La mia musica porta identità e certezza a un gruppo di giovani che non si identifica completamente con nulla. Questo gruppo si è identificato con questa batida perché era qualcosa di nuovo, né pienamente africano né europeo».

Hyperlocal Festival vedrà susseguirsi i DJ set dei pionieri DJ Nigga Fox and DJ Marfox, il primo nella giornata di sabato sul palco di Via Sile, il secondo durante l’Aftershow al Main Club. Mentre DJ Marfox ci aprirà un portale per esplorare l’anima multiforme della batida, attingendo alla sua essenza originale, DJ Nigga Fox ci catapulterà nel caos più totale con i suoi ritmi ultraterreni, turbolenti e imprevedibili.

It might not have been in its birthplace, but I did get to experience Batida a few years after these pictures were taken. The whirlwind of sinister, percussive beats cast a spell on me. Body and soul absorbed, I let my gelatinous limbs go free. My haunted dance responded to Vanyfox’s DJ set, one of the talents from the widely acclaimed Montreal-based collective Moonshine, and a leading voice among Batida’s youngest generation of artists. Self-described as a post-border, multidisciplinary music collective focused on African and Afro-diasporic club culture, Moonshine serves as a golden bridge between this music legacy and the various cities it regularly tours. It’s indeed thanks to their event at Dock B in Pantin on that Parisian winter night that I was first exposed to Batida, through Vanyfox.

According to Daviaa, Anglo-Portuguese producer and founder of the great radio show Na Tchada at Reprezent Radio, Vanyfox belongs to a long list of emerging and highly talented artists pushing the boundaries of Batida into unpredictable and equally fascinating directions. There’s DJ Tyson, part of a new trend slowing down the usual Batida’s 140 bpm; Danifox and Lycox, experimenting with adding vocals on the beats; Dariiofox, the closest to the original sounds of Batida, influenced by his brother DJ Nervoso; Nuno Beats and DJ Narciso, members of the more experimental RS Produções, mastering tension and release—and so on. Most are under Príncipe Discos, the Lisbon-based record label showcasing contemporary dance music from the city, its suburbs, and slums; widely recognised, and rightfully so, as one of the most exciting dance music projects on earth. Príncipe’s signature is Batida, an umbrella term standing for the multitude of results emerging, in short, from the encounter of regional styles from Lusophonic African countries and European electronic music.

With its geographical inception deeply rooted in Lisbon’s suburbs, Batida’s multifaceted sonic identity began to emerge amid the electronic music fervour of the early 2000s. In its early form, the emerging genre was an artisanal blend of Angolan kuduro and other African styles brought to Portugal by the Lusophonic diaspora, mixing with the new possibilities offered by the democratisation of early digital audio software. We could say that it all began with DJs Di Guetto Vol. 1, the first album launched in 2006 by a group including DJ Nervoso, DJ Marfox, and DJ Firmeza; all residents of Lisbon’s peripheral neighbourhoods, from Quinta do Mocho, now considered the scene’s cradle, to Quinta da Vitória, Baixa da Banheira, Queluz Massamá, and Barcarena. The compilation, available for free download online, spread widely and rapidly. It didn’t take long before they were invited to play in other European countries, soon expanding Batida’s outreach beyond the Portuguese capital.

The compilation was strategically released in September, starting the school year. Most of Batida’s pioneers were still in school when they laid the foundation for the genre, using cracked versions of FL Studio. Although they were still rare commodities, computers slowly became more available in the early 2000s, either at school or at friends’ houses. Amid the excitement of accessing early DAWs, DJs Di Guetto used this newly accessible technology to piece together the sonic influences they had been exposed to as members of Afro-descendant communities living in Lisbon’s peripheral neighbourhoods. These included first, second, and third-generation immigrants from Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, and São Tomé and Príncipe—all countries with a shared colonial history with Portugal. To grasp Batida’s role as one of the most significant contemporary sonic scenes, it’s crucial to understand its broader cultural context, starting with one of its main ingredients: Kuduro.

In the late ‘80s or early ‘90s, Angola was navigating the intermittent civil war that followed its independence from Portugal in 1974. Ceasefires saw Angola’s middle class travelling to Portugal and the rest of Europe, growing post-colonial exchanges between the two poles. As recalled by researcher Gerth Sheridan, this exchange introduced Luanda’s youth to a whole new array of imported recordings—found in street-side markets, clubs, and raves—and musical instruments. Soon enough, the emerging house and techno scenes taking over Europe influenced Angolan clubs, where DJs began incorporating these genres alongside American pop, and regional styles like kizomba and zouk.

Kuduro, which translates to “hard life” or very idiomatically to “hard ass,” emerged when producers took the next step by mixing genres, creating a new sound that would soon become part of the soundtrack of the final years of the Angolan civil war. As reflected by its lyrical bits, kuduro represented an outlet, through which to hope for a better future for the country; a sort of glue contributing to strengthening national identity. Angolan history and African media studies scholar Marissa J. Moorman importantly notes that kuduro has frequently been dangerously co-opted by governments and military officials for their political agendas. The genre reached cross-class popularity when working-class Luandans created their version—faster, harder, and with lyrics that articulated the experience of living in the musseques, Luanda’s shanty towns.

Kuduro was the main regional sound behind Batida, but not the only one that contributed to the genre’s frenetic rhythms. Aside from European influences, uptempo kuduro merges with Angolan tarraxinha, Cape Verdean funaná, and zouk—musical styles rooted in various Lusophone African regions which coincide with the Afro-descendant diaspora in Lisbon. Reversing the trend of the European scene influencing the birth of kuduro in Luanda, this diaspora’s cultural and sonic heritage became a core element for Batida’s pioneers. Diasporic configurations and their geography are thus intrinsic to Batida’s identity.

The creation of Príncipe Discos by Márcio Matos, José Moura, Nelson Gomes, and André Ferreira marked a definitive turning point in the scene’s internationalisation. The label launched in 2011 with DJ Marfox’s debut Eu Sei Quem Sou, which set the tone for Príncipe’s sonic identity and direction. That same year, Marfox became a key link between Príncipe and the peripheral neighbourhoods where Batida was gaining traction, recruiting the most talented and diverse emerging voices in the scene. Among the first recruits was DJ Nigga Fox, whose first release O Meu Estilo, according to Matos, signified a crucial juncture for the label, capturing the audiences’ attention. Following this, Nídia, DJ Firmeza, and DJ Nervoso joined the scene. By the mid-2010s, Príncipe DJs were streamed transcontinentally and performed at Sonar, Roskilde, and New York’s MoMA.

However, the scene’s identity remains closely tied to its geographical origins and the cultural and sociopolitical dynamics it embodies. “Car horns, fire alarms, percussive sounds, and indistinguishable chatter in Portuguese, Cape Verdean Creole, and Angolan slang”—much like an archive, as sociologist Otávio Raposo puts it, the neighbourhood’s atmospheric acoustics sampled in Batida’s tunes play a fundamental role. This “layer of sonic information” has the power, according to the researcher, “to inscribe silenced histories” and “systemically excluded bodies” into Portugal’s narrative and public sphere. As DJ Marfox once told Raposo, “My music brings identity and certainty to a group of young people who don’t fully identify with anything. This group identified with this batida because it was something new, not fully African nor European.”

Hyperlocal Festival will feature DJ sets from pioneers DJ Nigga Fox and DJ Marfox, with the former performing on Saturday on the Via Sile stage, and the latter during the Aftershow at the Main Club. While DJ Marfox will open a portal for us to explore Batida’s multifaceted soul, drawing from its original essence, DJ Nigga Fox will plunge us into complete chaos with his otherworldly, raucous, unpredictable beats.