La storia del grime trascende la musica in sé: è una storia di disparità economica, razzializzazione e urbanizzazione violenta; è una storia dove le forze dell’ordine antagonizzano comunità provenienti da aree di povertà e disagio. Ma è anche una storia di resilienza struggente, dove la musica è il mezzo attraverso il quale una comunità, consapevolmente o meno, ha creato uno spazio in risposta alla pressione claustrofobica della città che abitava. Nato e cresciuto in isolamento nell’East End, in particolare a Bow (E3), questo è un breve riassunto che dimostra come un genere musicale raramente possa essere più iperlocale di così. La parte virgolettata del titolo proviene dal terzo capitolo di Inner City Pressure: The Story of Grime, libro scritto dal giornalista e hardcore fan di lunga data Dan Hancox, che presenta un’approfondita analisi socio-politica del fenomeno musicale dell’East London. Per chi trovasse affascinante il racconto che segue, suggerisco di immergersi direttamente nel testo, che fornisce la maggior parte delle informazioni contenute in questo articolo. Ma per ora partiamo dalle basi.

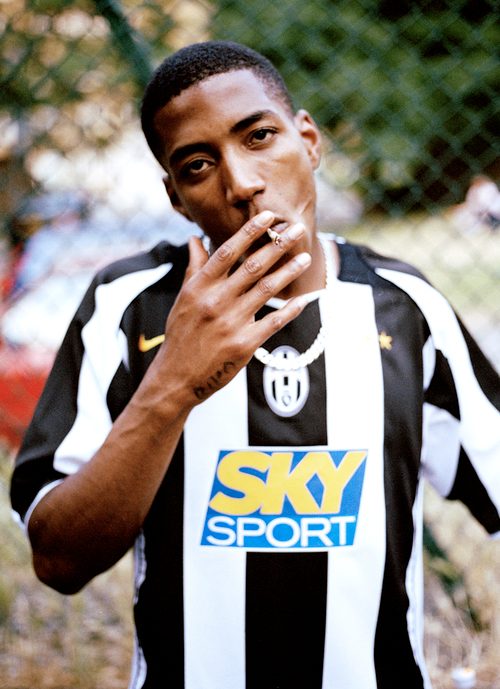

Come ogni altro genere che ha raggiunto il mainstream, il grime è conosciuto in tutto il mondo grazie a una manciata di artisti: Skepta, Stormzy, Dizzee Rascal e Wiley. Ma qual’era il suono del grime prima del suo successo commerciale, quando è stato prodotto per la prima volta? Figlio afrofuturistico indesiderato del movimento UK Garage, è una versione più oscura realizzata da persone che non erano abbastanza ‘cool’ per entrare alle feste UKG. Troppo grezzo, proprio come la palette sonora del genere, composta da batterie sincopate, melodie al neon, rullanti metallici, bassline distorte e voci incendiarie sputate con un’attitudine schizofrenica e aggressiva a un ritmo costante di 140 bpm.

Torniamo ora ai primi anni 2000, nei tre quartieri più disagiati di tutta l’Inghilterra: Hackney, Tower Hamlets e Newham, dove il sound si è affermato e ha preso il suo nome.

Prima di tutto: grime significa sporcizia. Se foste un musicista e qualcuno chiamasse la vostra musica in questo modo, probabilmente reagireste come la maggior parte dei DJ, dei produttori e degli MC della scena: vedendola come una mancanza di rispetto. C’è voluto un po’ di tempo, ma sorprendentemente il nome è rimasto. Come ha suggerito l’MC Nasty Jack in un documentario del 2006: «La maggior parte dei brani grime sono stati realizzati in case popolari sudice [grimy council estates]».

Di fatto, l’intera scena è nata nei ‘council estates’ — complessi edilizi di palazzi popolari, proprietà del governo affittate a residenti a basso reddito — tra la fine degli anni Novanta e l’inizio del nuovo millennio, in un’area identificata come “Inner East London”, storicamente un insieme di quartieri dove si trovavano varie industrie pesanti assieme al porto, per secoli punto di approdo di molti immigrati che arrivavano in città. L’incrocio di queste due caratteristiche ha reso per molti anni East London una comunità operaia incredibilmente multiculturale. Come si può immaginare, smog, inquinamento, polvere e sporcizia di ogni tipo caratterizzavano l’ambiente, e anche dopo i famosi sgomberi delle baraccopoli nella prima metà del XX secolo, l’area, entrata nel suo periodo post-industriale, è rimasta associata al senso di detriti delle industrie.

«Una scena parrocchiale, ossessionata dal senso del luogo.» — Simon Reynolds

Flash forward all’inizio del nuovo secolo, un gruppo di adolescenti – principalmente di origine africana o caraibica – si ritrova sul tetto di una casa popolare a sputare barre su strumentali inclassificabili, gasandosi a vicenda e commentando i beat come ‘dirty’ o ‘gritty’, dando ai loro crew nomi come “N.A.S.T.Y. crew”. Date queste premesse, non è assurdo tracciare un collegamento tra la storia urbana dell’area, le sensazioni evocate dall’ambiente, il bagaglio linguistico e semantico dei testi degli MC con quello che poi è diventato il nome del genere.

Tornando ai ‘council esatates’, questi grattacieli di 10 piani (o più alti) e i loro cortili sono spesso stati il primo parco giochi condiviso di questa generazione di MC, DJ e produttori. Per esempio, Dizzee Rascal — vincitore del Mercury Prize nel 2003 e primo MC grime a diventare mainstream — e Tinchy Stryder — storico MC della crew Ruff Sqwad — vivevano nel Crossways Estate, un famigerato complesso di 25 piani e tre torri situato a Bow. Considerando che negli anni ’80 il 42% delle case popolari si trovava nell’est di Londra, è ovvio che questi spazi urbani condivisi, insieme ai club giovanili e alle scuole, erano i nodi di una comunità che si legava attraverso l’emarginazione in un’area isolata, non servita nemmeno dalla metro. Come la definisce il critico musicale londinese Simon Reynolds: «Una scena parrocchiale, ossessionata dal senso del luogo».

Il genere si interseca con altri fenomeni della musica nera diasporica, attraverso un’eredità comunitaria che si estende ben oltre la generazione di questi ‘grime kids’. Molti dei loro genitori si conoscevano già dai tempi della scuola, alcuni suonavano anche insieme. Per esempio, i padri di Wiley, Jammer e Footsie erano nella stessa band reggae. Come una bomba a orologeria pronta a esplodere, il grime era in qualche modo codificato nel DNA degli artisti. Tuttavia, questa discendenza non è solo di sangue, ma è un’eredità musicale che si diffonde attraverso le frequenze sub-bass dei sound system, dagli antenati del dub e del reggae alla musica jungle, parente del grime dei primi anni Novanta. I grime kids sono cresciuti con la jungle e il terreno comune tra questi due generi risiede più nell’ambiente che nel suono stesso, in un elemento condiviso da molti generi musicali: la strada. Citando la figura paterna della jungle, MC Navigator: «Sai, è soprattutto la gente di strada che va alla jungle. […] In fin dei conti si tratta di persone che provengono da un contesto urbano e che vivono in comunità. Tutti li chiamano classe operaia o come si chiama, ma è sicuramente di strada».

Stesse persone, stesso background, stesso atteggiamento. Non a caso le prime apparizione di alcuni di questi artisti grime a sputare barre in un rave o in una radio pirata, sono avvenute su tracce jungle; artisti come l’MC preferito del tuo MC preferito, D Double E, il leggendario Wiley e il pioniere Riko Dan hanno fatto il loro esordio come MC proprio sulla jungle durante la loro adolescenza. Dal punto di vista musicale, la componente MC e l’atteggiamento adrenalinico e frenetico sono gli elementi che uniscono jungle e grime. Infine, ma non meno importante, sono state le radio pirata, le loro tecnologie e la loro logistica a collegare queste due correnti artistiche.

Definite da Dan Hancox come «l’ultimo bastione dell’auto espressione veramente autonoma della classe operaia urbana – autonoma nel senso che è possibile guadagnarsi da vivere con essa, senza l’approvazione o l’estrazione di profitti da parte delle industrie culturali britanniche consolidate, più bianche e ricche», le radio pirata erano centri di aggregazione per la musica che rifiutava di adattarsi ai canali mainstream. Trasmettendo soprattutto sezioni di musica rave e urban, mantenevano acceso il fuoco intorno alla produzione di forme d’arte subculturali. Tutto ciò che serviva era un trasmettitore FM, un’antenna, un posto dove allestire il proprio studio e una mentalità da pirata, vale a dire: essere sempre un passo avanti alle autorità; arrampicarsi sui tetti più alti e pericolanti per piazzare la propria antenna; essere sempre pronti ad avere un piano B per riprendere le trasmissioni – perché la tua antenna, ben visibile da tutti, a un certo punto verrà tirata giù dall’Ofcom, la polizia delle telecomunicazioni.

Geeneus e Slimzee, insieme agli altri pirati, crearono uno spazio di sperimentazione sonora e di espressione sociale che sarebbe durato per molti anni a venire.

Ogni nave pirata ha il suo capitano, e i comandanti della nave grime erano Geeneus e Slimzee, che da adolescenti giovanissimi, molto prima che il grime esistesse, fondarono Rinse FM nel 1994, nel periodo circa in cui la maggior parte delle radio pirata stava nascendo. La storia racconta che Geeneus e Slimzee si sono conosciuti alla stazione pirata di musica jungle Pressure FM, prima di essere cacciati (a quanto pare un adolescente Slimzee era già troppo bravo con i dubplate, mettendo in imbarazzo gli altri DJ). In seguito, i due decisero di fondare la propria stazione radio senza sapere esattamente cosa stessero facendo, incarnando così l’attitudine DIY ‘f**ck-all’ che divenne l’ethos principale del grime. La loro prima trasmissione avvenne a Bow, dalla Ingram House, palazzo di 18 piani a cinque minuti dall’appartamento di Slimzee, a cinque minuti da quello di Wiley e a cinque minuti da Roman Road.

Ci sono diversi motivi per cui le radio pirata sono un fenomeno così interessante da un punto di vista iperlocale. Innanzitutto, in ragione dei limiti tecnici, la trasmissione media copriva circa un paio di isolati dall’antenna. Il pubblico era dunque necessariamente locale e, per avere un’audience sostenibile, una buona quantità di persone doveva vivere nel raggio di trasmissione. È ragionevole dunque supporre che l’urbanizzazione composta di agglomerati abitativi e grattacieli di queste zone fornisse la giusta densità di popolazione per intrattenere una comunità sufficientemente ampia da essere interessata a sintonizzarsi e a mantenere attiva la stazione. Inoltre, le radio pirata erano apprezzate anche per la loro rilevanza locale, in quanto fornivano informazioni e pubblicità su eventi, attività commerciali e serate nei club dei dintorni.

Geeneus e Slimzee, insieme agli altri pirati, crearono uno spazio di sperimentazione sonora e di espressione sociale che sarebbe durato per molti anni a venire; un terreno fertile dove la scena poteva fiorire avendo il tempo di trovare la propria identità. Gettarono le basi di un movimento collettivista, fatto quasi esclusivamente per una cerchia ristretta, vincolata dalle possibilità e dagli orizzonti limitati che East London poteva offrire.

Come abbiamo accennato in precedenza, la musica della metà degli anni Novanta e oltre era la UK garage, un genere dance caratterizzato da melodie, ritornelli cantati, champagne poppin’ e dall’essere il più stiloso del club. Ma appena dietro l’angolo dei primi anni 2000 cominciarono a emergere alcuni supergruppi UKG più incentrati sugli MC. Crews in cui la figura del “gangsta rapper” era prominente, come la So Solid Crew – oggi qualcuno riconoscerebbe Asher D, uno dei principali MC della So Solid, come Dushane della serie Top Boy –, la Heartless Crew e la Pay As You Go Cartel – quest’ultima formata da Geeneus, Slimzee, DJ Target, Flowdan, Wiley e molti altri – iniziarono a fare apparizioni significative nelle classifiche. Sembrava che tutte quelle ore passate nello studio di Rinse FM fossero il punto di svolta verso una musica con al centro gli MC. Ancora una volta, la cosa più intrigante è che nessuno di questi giovani era consapevolmente intenzionato ad andare in questa direzione. Tuttavia, come suggerisce Geeneus in questo video, era tutto destinato ad accadere.

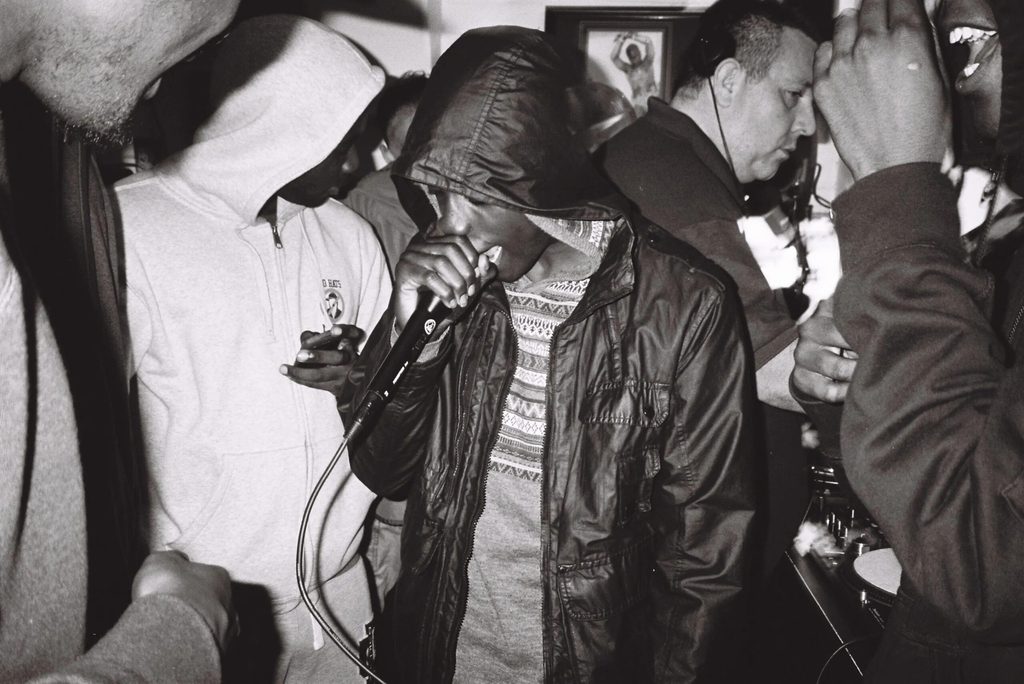

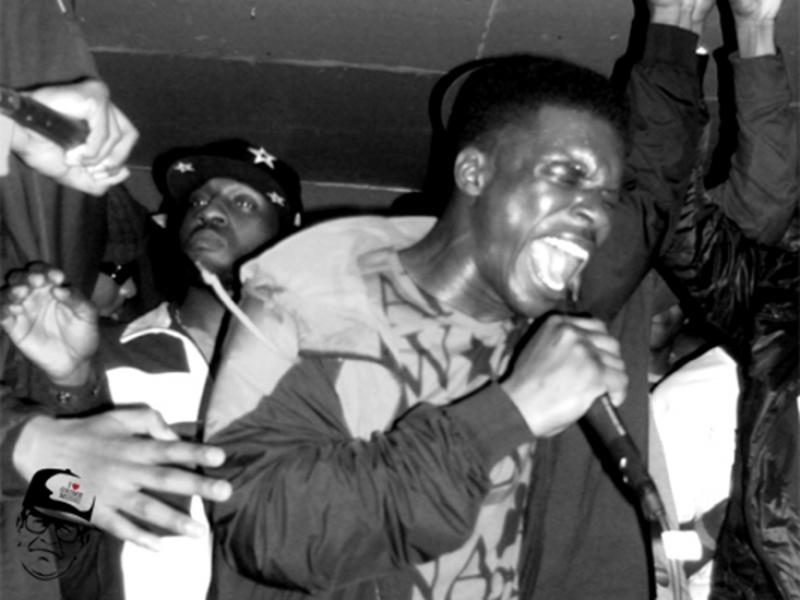

All’inizio del nuovo millennio nessuno sapeva dargli un nome ma tutti sapevano cosa stava succedendo: ogni domenica pomeriggio ci si poteva sintonizzare su Rinse FM per lo show di Slimzee e sentire la voce degli eroi locali attraverso le onde radio, intenti a sputare liriche aggressive l’uno contro l’altro e combattendo per la propria reputazione in un clash con il prossimo MC. La violenza però era esclusivamente lirica, sia in radio che nei rave. Gli ascoltatori si chiedevano che volto avessero queste voci, e sapevano che avrebbero potuto scoprirlo nel prossimo rave promosso dalla stessa stazione radio. Questo tipo di violenza musicale è stata spesso rifiutata dalle grandi etichette e criticata dalle autorità locali, ma ciò che queste autorità non hanno voluto capire è che era solo un riflesso della violenza presente nelle strade.

Con l’avvento degli anni Duemila le cose si sono fatte più cupe. Nel 2002 si è registrato il più alto numero di accoltellamenti mortali nelle strade nell’arco di un decennio: la violenza e la povertà non diminuiscono con l’aumentare della pressione della città. Tutto questo accadeva di fronte a Canary Wharf, il quartiere degli affari che, insieme ad altre cittadelle bancarie, rendeva la zona di ‘inner London’ la regione più ricca dell’Unione Europea. Nel frattempo, a pochi chilometri di distanza, i distretti di Hackney, Tower Hamlets e Newham – aree associate alla scena grime – erano i più poveri dell’intero Paese. Può la disuguaglianza sociale ed economica essere più estrema di così?

«A quel tempo, la gente era arrabbiata. Aveva perso fede – ‘wasn’t soulful’. È allora che il suono venne creato e conosciuto. Togli tutte le melodie, sbarazzatene. Alza i bassi, aggiungi più distorsione, tira fuori il dolore e la frustrazione.»

Durante un’intervista rilasciata dopo la vittoria del Mercury Prize nel 2003 per il suo primo album “Boy in Da Corner”, guardando Canary Wharf Dizzee ha commentato: «È in faccia a te. Ti prende per il culo. Ci sono persone ricche che si trasferiscono qui, persone che lavorano nella ‘City’. Si vede che non vivono come noi». Se è vero che la musica è un riflesso della società, non avrebbe avuto senso che la generazione grime producesse canzoni melodiche e gioiose, o che si vantasse di una vita al top del jetset stappando bottiglie di champagne. Come suggerisce Jammer – icona e pioniere della scena grime – in “8 Bar – The Evolution of Grime”: «A quel tempo, la gente era arrabbiata. Aveva perso fede – ‘wasn’t soulful’. È stato allora che il suono è stato conosciuto e creato. È allora che il suono venne creato e conosciuto. Alza i bassi, aggiungi più distorsione, tira fuori il dolore e la frustrazione».

La comunità grime ha affrontato a lungo l’antagonismo delle autorità. Dalla caccia ai pirati alla critica, fino agli attacchi che legavano questo fenomeno alla criminalità: le forze dell’ordine vararono e adoperarono politiche di ogni tipo, e come se non bastasse all’epoca erano statisticamente più propense a fermare e perquisire cittadini neri otto volte più di qualsiasi altro gruppo etnico. Anche la musica è stata presa di mira direttamente: nel 2014 Noisey ha prodotto un documentario condotto da JME – fratello di Skepta – intitolato “The Police vs Grime Music”. Il documentario è una simil inchiesta sul “Form 696”, un modulo di valutazione del rischio per eventi, che ha causato l’annullamento di molti concerti grime – tanti all’ultimo minuto – ritenuti troppo pericolosi per motivi arbitrari. Attivo dal 2005 e al 2017, il “Form 696” è stato una vera e propria minaccia per la scena: i locali erano intimiditi dal sequestro delle licenze, si perquisivano gli artisti, registrando i loro dati personali e infine negando loro gli spazi e la libertà di esibirsi. Qualcuno potrebbe fare un parallelismo con quanto accaduto ultimamente nei club tedeschi, dove, ad artisti che hanno mostrato il sostegno alla causa palestinese, è stata negata la possibilità di suonare, senza spiegazioni trasparenti.

L’energia del grime è un prodotto del suo ambiente, che alimenta la comunità con le sue politiche ricevendo un ritorno di fiamma. È la voce di chi non ha voce, della comunità operaia che proviene dalla “cultura delle case popolari” – ‘council estates culture’. A volte è anche la colonna sonora di proteste contro gli aumenti delle tasse universitarie e i tagli ai fondi pubblici, come nel caso dell’inno grime “Pow!” di Lethal Bizzle, un brano che per un breve periodo è stato anche bannato da alcuni club perché perché i promoter erano spaventati dal caos che creava nel dancefloor – il grime può essere una cosa pazza.

Oggi la scena è fiorente. Gli artisti sono passati al mainstream alle loro condizioni, mantenendo il contatto con le loro radici. Proprio come ai tempi delle serie di DVD come “Risky Roadz” e “Lord of the Mics” e dei ragazzini con una videocamera a mano che documentavano autonomamente la scena, negli ultimi anni sono spuntate molte pagine editoriali e d’archivio su Instagram, che hanno puntato maggiormente i riflettori sulla scena, dando così una seconda vita al genere su scala più ampia e creando più spazio per la prosperità della scena. Al di sopra di tutti troviamo forse DaMetalMessiah.

Visualizza questo post su Instagram

Il grime è il suono della resilienza collettiva che si riprende il suo spazio, o come spiega Dan Hancox: «“Buss” significa sparare un colpo di pistola, fare una mossa o colpire, esprimere se stessi – trovare spazio e libertà. Il grime, nella sua prima giovinezza, era eccitante perché claustrofobico, una cacofonia frenetica di beat e di stab di synth, che trasmetteva la tensione dei grattacieli, gli orizzonti e le possibilità limitate. Ma proprio come la vera claustrofobia, richiede libertà e spazio».

The history of grime transcends music per se: it’s about economic disparity, racialization and violent urbanization; it’s about the police and the government antagonizing communities originating from geographies of poverty and deprivation. But this is also a heartbreaking story of resilience where music is the medium through which a community, consciously or not, created more space in response to the claustrophobic pressure of the city it inhabited. Born and raised out of isolation in the East End, specifically in Bow (E3), this is a brief recap, proving that a music genre rarely gets more hyperlocal than this. The quoted part of the title comes from chapter three of Inner City Pressure: The Story of Grime: a book written by journalist and long-time hardcore fan Dan Hancox, presenting an in-depth socio-political analysis of the East London music phenomenon. For anyone who finds the following account compelling, I suggest diving directly into the text, which provides most of the information within this article. But for now, let’s start from the basics.

Like any other genre that made it to the mainstream, grime is known worldwide thanks to a handful of artists: Skepta, Stormzy, Dizzee Rascal and Wiley. But what did grime sound like before its commercial success, when it was first produced? Afrofuturistic unwanted child of the UK Garage movement, it’s a darker version made by people who weren’t cool enough to get into the polished and dress-coded UKG parties. Too raw to get in, just like the genre sonic palette, composed of syncopated drums, neon melodies, metallic snares, distorted basslines and arsonist vocals spit with a schizo, aggressive attitude at a steady tempo of 140 bpm. Now, let’s move back to the early 2000s, to the three most deprived boroughs in all of England: Hackney, Tower Hamlets and Newham, where the sound was established and given its name.

First things first: grime means dirt. If you were a musician and someone called your music this way, you’d probably react in the same way most DJs, producers and MCs from the scene did: feeling a general sense of disrespect. It took some time, but surprisingly the term stuck. As MC Nasty Jack suggested in a 2006 documentary: “Most grime tunes are made in a grimy council estate.”

Indeed, the whole scene sprouted from council estates — building complexes owned by the local government and rented to low-income residents —, between the late 1990s and the beginning of the new millennium, in an area identified as ‘Inner East London’, historically a complex of blue-collar boroughs, where one could find various heavy industries alongside the docks, which for centuries had been the landing point of many immigrants coming to the city. The clash of these two features made East London an incredibly multicultural working-class community for many years. As you can imagine, smog, pollution, grit and muck of all kinds characterized the environment, and even after the renowned slum clearances during the first half of the twentieth century, the area, entering its post-industrial period, maintained associations with the industries’ sense of debris.

Flash forward to the beginning of the new century: a bunch of teenagers — mostly African or West Indies descendants — are on a council estate rooftop, spitting over unclassifiable instrumentals, gassing each other up and commenting the beats as dirty or gritty, giving their crews names such as ‘N.A.S.T.Y. crew’. Given these premises, it’s not far-fetched to draw a connection between the area’s urban history, the sensations evoked by the environment and the MCs’ lyrical semantics and vocabulary to what eventually became the label-name of the genre.

Going back to council estates, these 10-storey (and taller) tower blocks and their courtyards often happened to be the first shared playground of this generation of MCs, DJs, and producers. For instance, Dizzee Rascal — the 2003 Mercury Prize awardee and first grime MC to go mainstream — and Tinchy Stryder — Ruff Sqwad crew historical MC — used to live in the Crossways Estate, an infamous 25-storey, three-tower complex located in Bow. Given that in the 1980s 42% of the city council homes were in East London, it’s obvious that these shared urban spaces, together with youth clubs and schools, were the nodes of a community bonding through marginalization in an isolated area, not even served by the tube. As London-born music critic Simon Reynolds defines it: «A parochial scene, obsessed with a sense of place.»

The genre intersects with other phenomena of black diasporic music, through a community heritage that extends far beyond the grime kids’ generation. Many of their parents already knew each other from school and some of them played music together: for instance Wiley’s, Jammer’s and Footsie’s fathers played in the same reggae band. Like a time bomb set to explode, grime was somewhat encoded in the artists’ DNA. Yet, this lineage isn’t only about blood, it’s a musical heritage spreading through the sound systems’ sub-bass frequencies, from its dub and reggae ancestors to grime’s early 1990s relative, jungle music. Grime kids grew up with jungle, and the common ground between these two genres lies more in the environment than the sound itself; an element shared by many music genres: the streets. Quoting jungle’s father figure MC Navigator: «Y’know and its mainly street people that go to jungle. […] At the end of the day it’s all about people that come from an urban background and live in communities. Everyone call them working class or what- ever, but it’s definitely from a street level.»

Same people, same backgrounds, same attitude. It’s not a coincidence that the first appearance of a few of these grime artists spitting bars in a rave or in a pirate radio station was over jungle tracks; artists like the MCs’ favorite grime MC, D Double E, the legendary Wiley and pioneer Riko Dan made their MC breakthroughs over jungle during their teenage years.

Music-wise, the MC component and the adrenaline-filled, fast-paced attitude are what link together jungle and grime. Last but not least, it was pirate radios, their technologies and logistics that connected these two artistic currents.

Defined by Dan Hancox as «the last bastion of truly autonomous, urban working-class self-expression — autonomous in the sense that it is possible to make a living from it, without the approval, or profit extraction, of the whiter, wealthier established British culture industries.» pirate radios were hubs for music that didn’t fit into mainstream channels. Broadcasting sections of rave and urban music especially, pirate radios kept the fire burning around the production of subcultural art forms. All you needed was an FM transmitter, an aerial, a place to set up your studio and that pirate mentality. This meant being a step ahead of authorities, climbing up the sketchiest and highest rooftops to set up your aerial; always being ready to have a plan b to resume broadcasting, because your antenna, well visible by everyone, will eventually be taken down by the Ofcom, the telecommunications police.

Every pirate ship has its captain(s), and the grime vessel’s commanders were Geeneus and Slimzee, who as very young teenagers long before grime even existed, set up Rinse FM in 1994 around the time most pirate radios were getting started. As the story goes, Geeneus and Slimzee met at the jungle pirate station Pressure FM before they eventually got kicked out (apparently a teenage Slimzee was already too good with dubplates, embarrassing the other DJs). Following this, the two decided to set up their own pirate radio station without knowing exactly what they were doing, thus embodying the DIY f**ck-all attitude which became the main ethos of grime. Their first broadcast took place in Bow, from the 18-storey-high Ingram House, five minutes from Slimzee’s flat, five minutes from Wiley’s flat and five minutes from Roman Road.

There are several reasons why pirate radios are a phenomenon that is so hyper-locally interesting. First of all, due to technical shortcomings, the average broadcast would only reach a couple of blocks from the antenna. This meant that your audience had to be local and for a station to maintain a sustainable audience, quite a good amount of people had to be living within the broadcast radius. It makes sense to assume that the urbanization of house agglomerates and tower blocks gave the right population density to entertain a community wide enough to be interested in tuning in and keeping the station active. Furthermore, pirate radio stations were also appreciated for their local relevance because they were providing information and advertisements about local community events, businesses, and club nights.

Geeneus and Slimzee, together with the other pirates, created a space of sonic experimentation and social expression for many years to come; a fertile soil where the scene could flourish having the time to find its own identity. They laid down the basis for what would become a collectivist movement, almost exclusively made for an inner circle constrained by the narrow chances and horizons that East London could offer.

As we mentioned earlier, the music of the mid-1990s and beyond was the UK garage, a dance music genre characterised by melodies, sung choruses, champagne poppin’, and being the flyest in the club. But just around the corner of the early 2000s, some MC-centered UKG supergroups began to emerge. Crews where the figure of the gangsta rapper was prominent, such as So Solid Crew — today someone would recognize Asher D, one of the main MCs from So Solid, as Dushane from Top Boy series —, Heartless Crew and Pay As You Go Cartel — the latter formed by Geeneus, Slimzee, DJ Target, Flowdan, Wiley and many more — began to make significant appearances in the charts. It seemed that all those practice hours spent in the Rinse FM studio were the shift toward a more MC-centered music was finally taking shape. Once again, the most intriguing thing is that none of these youths ever meant to go in this direction. Nonetheless, as Geeneus suggests in the following video, it was all meant to be.

Beginning of the new millennium, no one had a name for it but everyone knew what was going on: every Sunday afternoon you could tune into Rinse FM and hear the voice of local heroes through the airwaves, fighting aggressively against each other for their reputation but only clashing with the next MC. Violence was exclusively lyrical whether in radio or in the rave.

Listeners might wonder what their faces looked like, and they might have discovered this in the next rave promoted by the very same radio station. This kind of musical violence has often been refused by major labels and criticized by local authorities, but what they failed to understand is that it was just a reflection of the violence present in the streets.

Things were getting a bit darker with the start of the new century. For instance, 2002 saw the highest number of fatal stabbings in the streets over a decade: violence and poverty do not decrease as the pressure increases. All of this was happening in front of Canary Wharf, the business district that, along with other bank citadels, made inner London the richest region in the European Union around the time. Meanwhile, just a couple of miles away, the boroughs of Hackney, Tower Hamlets and Newham—areas associated with the grime scene—were the most deprived of the whole country. Can social and economic disparity get any more extreme?

During an interview after winning the Mercury Prize in 2003 for his first album Boy in Da Corner, looking at Canary Wharf from his bedroom Dizzee commented: “It’s in your face. It takes the piss. There are rich people moving in now, people who work in the City. You can tell they’re not living the same way as us.”

If it’s true that music is a reflection of society, it wouldn’t really make sense for the grime kids to produce melodic and joyful songs singing about happiness, or to be boasting about their life at the top of the jetset, poppin’ champagne bottles. As Jammer – grime scene icon and pioneer – suggests in 8 Bar – The Evolution of Grime: “At that time, people was upset. People wasn’t feelin’ that soulful. That’s when the sound become known and created. Let’s just take all the melodies off, just get rid of them. Let’s turn the bass up, add more distortion, get the pain out, get the frustration out.”

The grime community has long faced antagonism from the authorities. From chasing pirates to criticizing and attacking this musical phenomenon as crime related, policies have been of any kind from the control authorities, who at the time were more likely to stop and search black citizens eight times more likely than any other ethnic group. Even grime music itself has been directly targeted: in 2014 Noisey produced a documentary hosted by JME — Skepta’s brother — called The Police vs Grime Music. The documentary investigated ‘Form 696’, a Promotion Event Risk assessment which caused the cancellation of many grime shows deemed too dangerous on arbitrary grounds. Active between 2005 and 2017, ‘Form 696’ has been a proper threat to the scene, menacing venues to strip off their licenses, searching artists, recording their personal details and ultimately denying them spaces to perform and sustain their life through music. Someone could draw parallelism to what’s been happening lately in German clubs with artists trying to show support for the Palestinian cause being denied the chance and space to play with last-minute cancelled shows.

Grime’s energy is a product of its environment, fueling the community with its policies and getting backfire from it. It’s the voice of the voiceless, the working-class community coming from the ‘council estate culture’. Sometimes even the soundtrack during protests against university tuition raises and public fundings cuts, such as for the grime anthem Pow! by Lethal Bizzle, a track that for a short period was also banned from some clubs’ because they were scared of the hype it created on the dancefloor – grime can be a mad thing.

Today the scene is thriving. The artists have crossed over to the mainstream on their own terms, keeping in touch with their roots. Just like back in the days with DVD series such as Risky Roadz and Lord of the Mics and kids with a handycam independently documenting the scene, in the last few years many editorial and archival instagram pages have popped, putting a bigger spotlight on the scene, thus giving a second life to the genre on a wider scale and creating more room for the scene to thrive. Above them all we perhaps find DaMetalMessiah.

Grime is the sound of collective resilience that buss’ its space back, and as Dan Hancox explains: «‘Buss’ meaning to fire a gunshot, bust a move, or strike out, express yourself – find space and freedom. Grime in its first flash of youth was thrilling because it was claustrophobic, a hectic cacophony of beats and synth stabs, channeling the high-rise tension of tower blocks, the limited horizons and possibilities. But just like real claustrophobia, it demands freedom – and space.»