È un errore comune pensare che le frange più estreme di un genere musicale – le interpretazioni più rumorose e più radicalmente feroci – nascano dal desiderio di deviare, di pervertire, di corrompere i presupposti base del genere. Per l’appassionato di musica medio, infondere rumore nel canone prestabilito e farcirlo di dissonanze è pura distorsione, una profonda mancanza di rispetto verso i fondatori del genere e i loro sforzi.

Più spesso, in realtà, succede il contrario, specialmente nella musica elettronica. Quando i generi diventano più duri e più rumorosi, di solito è perché è arrivata una nuova generazione desiderosa di ricreare la stessa urgenza, lo stesso senso di stupore perverso e di pericolo che li aveva attratti al genere in primis, nonché la voglia di tenere viva quella cultura facendo un passo in avanti rispetto alla radicalità stessa delle sue origini.

È il caso della breakcore: per quanto chimerico e difficile da definire – guardando al suo insolito percorso evolutivo –, il genere nasce come tentativo di usare i linguaggi del caos e dell’aggressività per giocare a rialzo con la sound system culture inglese. Nelle sue prime iterazioni la breakcore aumentava quantitativamente gli elementi anti-musicali e le spiazzanti decostruzioni ritmiche già presenti nella jungle, non per demolirne o sopprimerne il groove, quanto per aumentarne esponenzialmente la presenza e il peso, attingendo dall’uso di distorsioni sempre più aggressive e dai tempi rapidi che caratterizzavano le frange più dure della techno.

La breakcore arrivava a dichiarare che quel futuro era giunto molto prima del previsto e che la distopia tanto temuta stava già permeando ogni aspetto della società occidentale.

A differenza della setta IDM e dei suoi (spesso fraintesi) esperimenti di astrazione, la prima generazione di produttori breakcore puntava a conservare l’esplorazione sonora attorno alla danza. Non importava quanto strani e cacofonici fossero i beat: l’intento era scuotere corpi ignari con una scarica di energia. Nell’oscurità intrisa di volume della cultura rave europea degli anni Novanta, la prima breakcore emerse come una ritmo-macchina vorticistica – alimentata tanto dalla forza centripeta delle frequenze sottosoniche e dalla virulenza dei ritmi sincopati, quanto dall’eccitazione generata dal puro caos e dalla distorsione.

Se per il compianto Mark Fisher «la geografia selvaggia della jungle sembrava derivare dalla fantascienza distopica […] costruendo la propria fiction sonora afro-futurista e cyber-gotica, ambientata nelle gallerie fatiscenti di un futuro prossimo», la breakcore arrivava a dichiarare che quel futuro era giunto molto prima del previsto e che la distopia tanto temuta stava già permeando ogni aspetto della società occidentale. Il Terminator era stato sabotato, era impazzito e mutato in qualcosa di grottesco. Aggirarsi tanto al di fuori della fortezza della società di controllo quanto lontano dai confini simbolici delle forme consolidate di ribellione dava l’opportunità di operare a un nuovo livello di libertà, sperimentando nuovi modi di ballare, interagire e creare. In sostanza, si trattava di un modo per mantenere viva la vera fiamma del rave, nonostante la già dilagante gentrificazione della musica dance.

A metà anni Novanta, Londra era ancora indubbiamente la terra promessa per ogni fazione della cultura rave: dalla house alla techno, dalla dancehall alle filiazioni più gettonate della jungle – come la drum & bass e la sua miriade di sottogeneri. Dopo l’approvazione del famigerato Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994, la città divenne anche la sede di alcuni sound system altamente militanti, che organizzavano costantemente feste illegali attorno alla tangenziale M25. Al tempo, anche crew leggendarie come gli Spiral Tribe, ormai quasi sul punto di trasferirsi in Francia, sparavano spesso dalle loro casse dei set rumorosi, velocissimi e zeppi di breakbeat, fondendo la frenesia dell’hardcore techno con le contorsioni poliritmiche della jungle. Solo un anno dopo, tribe pionieristiche come gli Hekate avrebbero iniziato ad allargarne i confini, sfornando tra i brani più duri, oscuri, distorti e sperimentali sulla piazza.

Le radici della scena erano però saldamente radicate nel quartiere working class e multiculturale di Brixton. I gruppi o gli individui più radicali che preferivano organizzare i loro rave in spazi chiusi — piuttosto che nelle vaste fabbriche abbandonate dove si aggiravano le tribe —, avevano poco accesso (e spesso poco interesse) nei club tradizionali. Preferivano gravitare attorno ai numerosi squat che avevano preso possesso degli edifici abbandonati di South London, ripopolandoli per scopi pratici e politici. Il loro spirito DIY era il contesto perfetto per chi concepiva il divertimento come atto politico, cercando di unire musica, militanza e altre forme di sperimentazione culturale multimediale. Fu in uno di questi spazi liberi – una casa vittoriana di tre piani su Railton Road, che una comunità di anarchici aveva rinominato 121 Center – che il party mensile Dead By Dawn ebbe inizio. Era il 1994 ed è più o meno lì che è cominciato tutto.

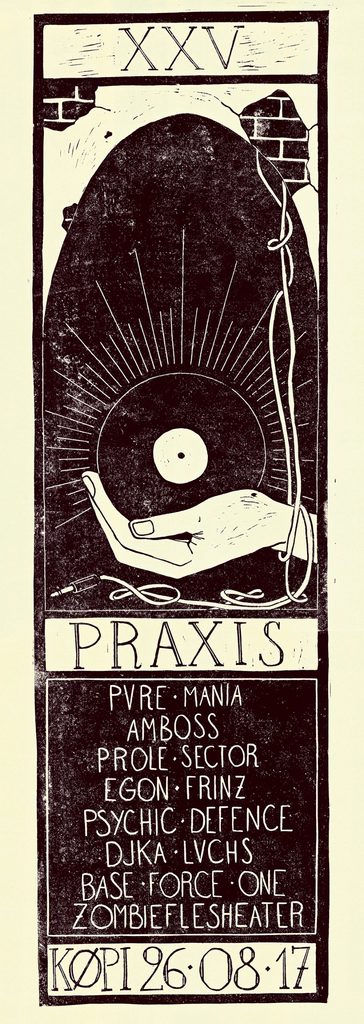

Il progetto venne avviato da un collettivo che si faceva chiamare The Invisible College, riunito dal musicista, DJ, attivista e visionario svizzero Christoph Fringeli, la cui pionieristica etichetta Praxis aveva già pubblicato un primo lotto di dischi piuttosto violenti. Dead By Dawn non era solo un rave, ma anche uno spazio per discussioni politiche, esplorazioni tecnologiche, mostre d’arte e installazioni. Ciononostante, divenne rapidamente noto soprattutto come il luogo dove si poteva ascoltare la musica dance più veloce, dura e radicale di tutta Londra. Al tempo, però, questo significava quasi esclusivamente beat a cassa dritta. I resident (DJ Terro, Deviant, Sentinel e lo stesso Fringeli), e gli oramai leggendari ospiti di quelle prime feste, come Somatic Responses, Sonic Subjunkies, Crystal Distortion, Aphasic e, soprattutto, DJ Scud, suonavano una miscela di gabber rumorosa, techno oscura e frenetica e industrial accelerata. Nei rari casi in cui comparivano dei breakbeat o influenze ragga, questi erano accolti con stupore, se non addirittura con disprezzo, dai più punkabbestia.

Ironicamente, i semi della contaminazione tra il continuum post-ragga e le sperimentazioni più rumorose non stavano germogliando a Londra, ma in Germania, tra Francoforte e Berlino. Fu tra le prime uscite dell’etichetta Force Inc. di Achim Szepanski (e le sue numerose sub-labels come Position Chrome, Riot Beats e Mille Plateaux) che apparvero i primi 12” in cui la jungle veniva spinta verso le sue conseguenze più estreme. La maggior parte di questi dischi erano prodotti tutti dallo stesso artista: un certo Alexander Wilke, AKA Alec Empire. Nato e cresciuto a Berlino, Empire iniziò a organizzare feste nella capitale tedesca con il Bass Terror Soundsystem, fondato insieme al vocalist e DJ Carl Crack, e presto avviò la propria etichetta, l’influente Digital Hardcore Recordings. Inizialmente guidato da uno spirito radicale simile a quello di Praxis e Dead By Dawn, Empire avrebbe poi mirato alla celebrità mainstream (principalmente attraverso la leggendaria band Atari Teenage Riot) per cadere poi in disgrazia, sia dal punto di vista artistico che a livello di impegno politico.

Le influenze e i dischi iniziarono a rimbalzare avanti e indietro tra Brixton e Kreuzberg, ed espandendosi in nuovi territori. La scena stava maturando al punto che, nel 1996, Dead By Dawn passò dall’essere pubblicizzato come “techno speed core party” a una proposta fatta di “elettronica sperimentale, dark breaks, harshcore”. Una figura chiave in questo cambiamento di paradigma fu il già citato DJ Scud, nome reale Toby Reynolds. Londinese, Reynolds era passato non poche volte da Berlino, esplorandone gli annebbiati – e all’epoca scarsamente popolati – club, e si era particolarmente innamorato dell’approccio al DJing tagliente e creativo della underground star locale Tanith.

Reynolds inizialmente frequentava Dead By Dawn solo per ballare. Man mano però che la sua collezione di dischi cresceva, cresceva anche il desiderio di far girare quei dischi in pubblico e persino quello di crearne di propri, cosa che si sarebbe realizzata di lì a poco. Oltre a diventare una presenza fissa nelle lineup di DBD, Reynolds iniziò a produrre e pubblicare musica con l’aiuto di un altro habitué del 121 Center: Jason Skeet. Reynolds adottò il nome d’arte DJ Scud, mentre Skeet iniziò a farsi chiamare Aphasic, e insieme fondarono un’etichetta di nome Ambush, di cui ogni singola uscita sarebbe istantaneamente diventata un classico.

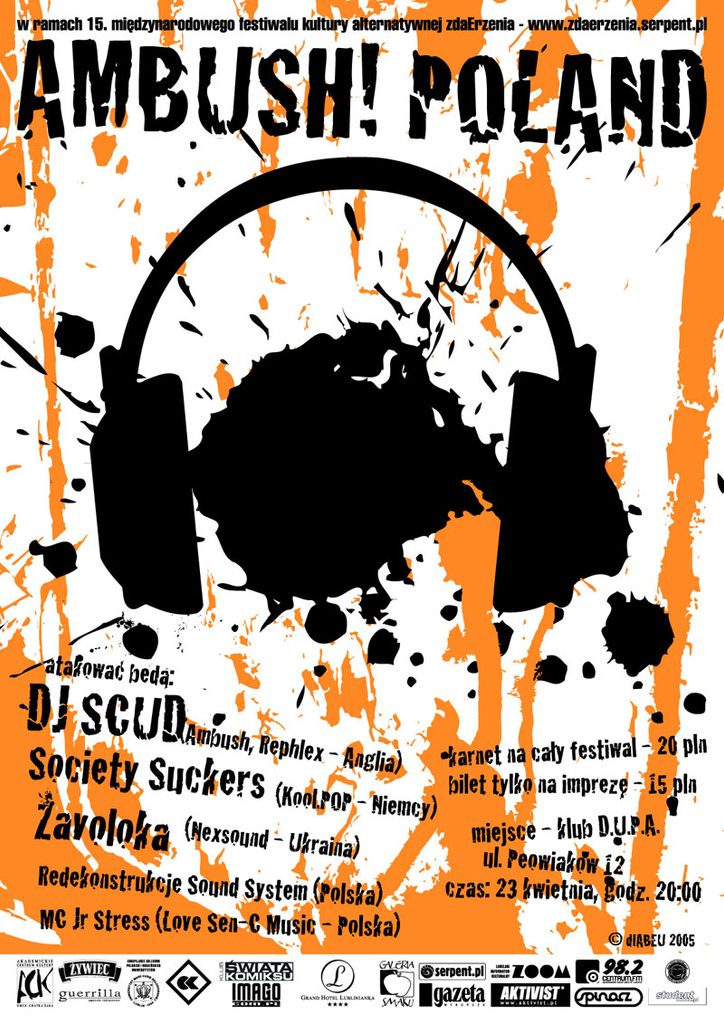

Per gli appassionati di breakcore non è un mistero quanto Reynolds sia stato fondamentale nell’evoluzione del genere, non solo per esserne stato uno dei migliori DJ e producer, ma anche per averne consolidato due, apparentemente antitetici, aspetti chiave: la sua imprevedibilità creativa e le radici nella cultura dance giamaicana. L’approccio di Reynolds alla produzione musicale era infatti stato plasmato dalla partecipazione regolare al Carnevale di Notting Hill, dove era rimasto affascinato dalla magnificenza dei brani che esplodevano dai massicci sound system caraibici. Reynolds usò rumore, distorsione e sperimentazione per emulare lo stupore che quei brani suscitavano in lui. Questo lo portò a sviluppare un suono distintamente personale, che evolse e mutò disco dopo disco, suonando tuttora fresco e originale. Il pubblico dell’IDM se ne accorse, al punto che, nel 2003, Aphex Twin decise di pubblicare una raccolta di brani di Scud sulla sua etichetta, Rephlex.

Fu proprio a un Dead By Dawn nell’agosto del 1995, che Scud fece un incontro fortuito che avrebbe esportato la breakcore in nuovi territori. A quella festa Toby fece infatti amicizia con Riccardo Balli, un giovane straight-edge italiano che, fino ad allora, aveva fatto parte di un paio di band hardcore punk, aveva bazzicato la scena noise locale e si era occupato di gestire l’infoshop del centro sociale LINK Project a Bologna, la sua città natale. Balli aveva appena scoperto la breakcore ed era rimasto entusiasmato dal suo potenziale. Per sua stessa dichiarazione, Balli aveva finalmente trovato un modo «per uscire dall’impasse del puro rumore, dal tempo stagnante, attraverso il funk, non come un genere musicale, ma come un brivido che fa scuotere il culo». In altre parole, aveva trovato una nuova via al terrorismo sonico e al sabotaggio culturale attraverso un linguaggio che parlava prima di tutto al corpo.

Balli era già entrato in contatto a Bologna con alcune frange del movimento neo-situazionista come il Luther Blisset Project, ma fu a Londra che divenne membro dell’Association of Autonomous Astronauts, un gruppo radicale orientato verso la ricerca sullo spazio, e legato anche ad altre figure della scena breakcore. Con il suo incrocio di cultura rave, politica d’avanguardia (spesso incarnata da personaggi come Stewart Home) e anti-arte sperimentale, Dead By Dawn diventò presto una seconda casa per Balli. Poco dopo, Scud gli insegnò a fare il DJ e da lì apprese rapidamente le tecniche più radicali e complicate del turntablism. A quel punto Riccardo Balli era ormai diventato DJ Balli, pronto a tornare in Italia e presentare alla scena underground globale il suo singolare stile di breakcore“alla Bolognese”.

«Breakcore può essere qualsiasi cosa che non sia rilassata e monotona, o che rifletta, celebri, o completi lo status quo».

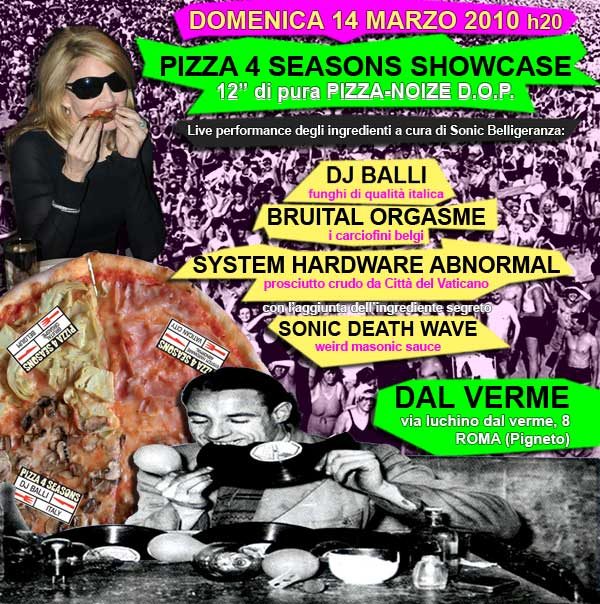

Quando però il genere arrivò in Italia, un paese la cui vasta scena free party era profondamente legata ai movimenti controculturali e alla sinistra radicale, rimase per lo più un’iniziativa individuale. Balli iniziò presto a portare tutti i suoi amici di Dead By Dawn al Link Project. Poi, nei primi anni 2000, cominciò a organizzare feste di breakcore presso il centro sociale di Vicolo Bolognetti nel quartiere di San Vitale a Bologna, rimanendo a lungo l’unico vero promotore del genere in tutto il paese. Non ci mise molto a lanciare a sua volta un’etichetta: Sonic Belligeranza, un manifesto per la sua visione di ciò che la breakcore poteva diventare: un po’ qualsiasi cosa, in pratica. Superando le radici più orientate verso il rave e abbracciando l’idea situazionista di rivolta culturale giocosa, Balli utilizzava la breakcore come mezzo per sperimentare, decostruire e sovvertire elementi della cultura popolare, tramutandoli in sgradevoli e inquietanti strumenti di deprogrammazione di massa. Affrontando ogni nuovo progetto con lo stesso radicalismo, contribuì a trasformare il genere in qualcosa di sonoramente sfuggente e concettualmente difficile da definire. La sua visione, sebbene distinta, completò quella di Scud, creando una cacofonia non solo musicale ma anche culturale.

Diversi anni dopo, e probabilmente a causa dell’influenza del nuovo approccio di Balli, la breakcore è diventata quasi irriconoscibile per i veterani del genere. Ha attraversato le contaminazioni eclettiche simil-IDM introdotte nei primi anni 2000 da artisti come Venetian Snares, Kid 606 e Bong-Ra, ha assorbito l’influenza dank della cultura dei meme e della musica trash di internet, per arrivare a un recente revival infuso da un lato di elementi hyperpop ed estetiche ispirate ai manga, e dall’altro di un doomerismo ambient caricato a benzo. Tuttavia, per chi sa riconoscerla, è facile ritrovare in in innumerevoli artisti e generi l’influenza della breakcore primordiale, o almeno una forte affinità con il suo spirito. E non è infrequente che si tratti di scene molto lontane dalle capitali della musica dance europea. Dopotutto, come recitava una newsletter della Praxis, breakcore “può essere qualsiasi cosa che non sia rilassata o monotona, o che non rifletta, celebri, né accompagni lo status quo”.

Hyperlocal Festival vedrà la partecipazione sia di DJ Scud che di DJ Balli, dove parteciperanno come ospiti musicali e si confronteranno in una discussione sulla storia, la politica e l’impatto culturale del breakcore moderata dall’autore.

It’s a common misconception that the more extreme fringes of a musical style—its noisier, most radically ferocious interpretations— emerge from a desire to deviate, pervert, or corrupt the genre’s basic premises. To the average music enthusiast, infusing an established canon with noise and layering it with dissonance is seen as distorting it, a sign of profound disrespect towards its pioneers and their efforts.

More often, what happens is the opposite, especially in electronic music. When genres become harder and noisier, it’s often because a new generation has come around, longing to recreate the same urge, the same sense of twisted wonder and adventurous danger that attracted them to the genre in the first place. It’s a desire to keep the culture alive by one-upping its initial, radical newness.

Such is the case with breakcore: as chimeric and difficult to define as the genre has become — following its unconventional evolutionary path —it originated as an attempt to use chaos and aggression as tools to raise the ante in UK sound system culture. In its earliest iterations, breakcore increased the number of anti-musical elements and mind-boggling rhythmic deconstructions already present in jungle, not to demolish or suppress its groove, but to exponentially enhance its presence and weight. It also drew from the increasingly aggressive distortion and rapid tempos happening in the hardest edges of techno.

Unlike the IDM sect and its (often misunderstood) experiments in abstraction, the first generation of breakcore producers aimed to keep the focus of their free-ranging sonic exploration on the dance. No matter how weird and cacophonic the beats were, it was meant to jolt unsuspecting bodies into motion with a surge of energy. In the volume-drenched darkness of 90s European rave culture, early breakcore emerged as a vorticist rhythmachine— driven as much by the centripetal force of sub-bass and the infectiousness of syncopation, as by the excitement of pure chaos and distortion.

If, for the late Mark Fisher, “jungle’s feral geography seemed as if it was derived from dystopian science fiction” and the genre “constructed its own Afro-futurist and cyber-gothic sonic fiction, set in the derelict arcades of a near future,” breakcore arrived to state that the future had come far sooner than expected and that the dreaded dystopia was already permeating every aspect of Western society. The Terminator had been sabotaged, gone mad, and mutated into something grotesque. Dwelling both outside the fortress of the society of control and far from the symbolic confines of then-consolidated modes of rebellion meant operating at a new level of freedom, experimenting with new ways to dance, interact, and create. It was ultimately a way to keep the true flame of rave alive, despite the already rampant gentrification of dance music.

In the mid-1990s, London was undoubtedly still the promised land for any sect of rave culture, from house and techno to dancehall and jungle’s more popular offshoots like drum & bass, along with their myriad of subgenres. After the infamous Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994 was passed, the city also became home to some highly militant sound systems, constantly organising illegal parties around the M25 motorway. At the time, even legendary crews like Spiral Tribe, who were by then on the verge of relocating to France, had their speakers blasting breaky, noisy, and fast sets that fused the breakneck speed of hardcore techno with the polyrhythmic contortions of jungle. Just a year later, pioneering tribes like Hekate would start pushing the envelope, championing the hardest, darkest, most distorted, and experimental tracks on the scene.

But the roots of the scene were firmly planted in the working class, multicultural neighbourhood of Brixton. The most radically minded among the crews or individuals who preferred to set their raves in enclosed spaces —rather than in the vast, abandoned warehouses where the tribes roamed —had little access to (and often little interest in) regular clubs. Instead, they preferred to gravitate around the innumerable squats that had taken over South London’s abandoned buildings, repopulating them for practical and political purposes. The DIY countercultural spirit of the radical movement actually served as the perfect backdrop for those who saw partying as a political act, seeking to merge music, militancy and other forms of cross-media cultural experimentation. It was at one of these free spaces — a three-storied Victorian house on Railton Road that a community of anarchists had renamed the 121 Center — that the monthly Dead By Dawn parties started taking place. That was 1994 and it’s more or less where it all started.

The project was initiated by a collective that called itself The Invisible College, brought together by Swiss musician, DJ, activist and all-out visionary Christoph Fringeli, whose seminal label Praxis had already released its first batch of hard-hitting records. Dead By Dawn was not just a rave, but also a space for political discussions, technological explorations, art exhibitions, and visual installations. Nonetheless, it quickly became known prevalently as home to the fastest, hardest and most radical dance music you could hear in all of London. At the time, this almost entirely meant four-to-the-floor beats. Its residents (DJ Terro, Deviant, Sentinel, and Fringeli himself) along with now-legendary figures that played at those early parties, like Somatic Responses, Sonic Subjunkies, Crystal Distortion, Aphasic and, most notably, DJ Scud, played a mix of noisy gabber, frantic dark techno, and sped-up industrial. If any breakbeats or ragga influences appeared at those early parties, they were met with bemusement, if not outright scorn by the crusty attendees.

Ironically, the seeds for the contamination between the post-ragga continuum and the noisier side of things were being planted not in London, but in Germany, between Frankfurt and Berlin. It was among the early releases of Achim Szepanski’s Force Inc. label (and its many sub-imprints like Position Chrome, Riot Beats, and Mille Plateaux) that the first 12”s appeared, pushing jungle to its extreme consequences. Most of these records were produced by the same guy: Alexander Wilke, AKA Alec Empire. Born and raised in Berlin, Empire began organising parties in the German capital with the Bass Terror Soundsystem, which he founded alongside vocalist and DJ Carl Crack, and would soon launch his own label, the highly influential Digital Hardcore Recordings. Initially driven by a radical spirit similar to that of Praxis and Dead By Dawn, Empire would eventually aim for mainstream stardom (mainly through legendary band Atari Teenage Riot) and ultimately experience a fall from grace, both artistically and politically.

Influences and records started bouncing back and forth between Brixton and Kreuzberg, eventually expanding into new territories. The scene matured, and by 1996, Dead By Dawn had shifted from being advertised as a “techno speed core party” to promoting “experimental electronics, dark breaks, harshcore.” A key figure in this paradigm shift was the aforementioned DJ Scud, real name Toby Reynolds. A Londoner, Reynolds had also spent considerable time in Berlin, exploring its foggy and —at the time– scarcely populated clubs, and became especially enamoured with local underground star Tanith’s hard-edged and creative approach to DJing.

Reynolds initially attended Dead By Dawn just to dance, but as his record collection grew, so did his desire to make those records spin in public and even create his own. All of it would soon become reality. In addition to becoming a regular in the DBD lineups, he began producing and releasing music with the help of another 121 Center regular Jason Skeet. While Reynolds adopted the monicker DJ Scud, Skeet called himself Aphasic, and together they founded a label called Ambush, with each release instantly becoming a classic of the genre.

It is no mystery to any breakcorehead how important Reynolds was to the genre, not only by being one of its best DJs and most creative producers but also by defining it as both creatively unpredictable and firmly rooted in Jamaican dance culture. His approach to music-making was shaped by his regular attendance at the Notting Hill Carnivals, where he was captivated by the marvellous tracks blasting from the massive Caribbean sound systems. He used noise, distortion and experimentation to emulate the awe those tracks generated in him. This led him to develop a distinctly personal sound that evolved and mutated with each release and remains incredibly fresh to this day. The IDM crowd took notice, and in 2003, Aphex Twin decided to release a collection of Scud tracks on his own label, Rephlex.

At Dead By Dawn in August 1995, Scud had a fortuitous meeting that would end up bringing breakcore to a new country. At that party, Toby met and became friends with Riccardo Balli, a young straight-edger from Italy who was then involved in hardcore punk bands, the local noise scene, and running the infoshop at LINK Project, a squatted cultural centre and music venue in his hometown of Bologna. Balli had just discovered breakcore and was galvanised by its potential. In his own words, he had finally found a way “to escape the dead-end of pure noise, which had been stagnating for ages, through funk, not as a musical genre, but as a goosebump that makes your ass shake.” In other words, he had found a means of sonic terrorism and cultural sabotage in a language that communicated with the body first.

Balli had already been in contact with fringes of the neo-situationist movement such as the Luther Blisset Project in Bologna, but it was in London that he became a member of a radical space-oriented dis-organization named Association of Autonomous Astronauts, a group also connected with other figures in the breakcore scene. At Dead By Dawn, with its crossover of rave culture, avant-garde politics (often personified by infamous characters like Stewart Home) and experimental anti-art, he found a new home. Soon after, Scud taught him how to DJ, and he quickly mastered the most radical and challenging techniques of turntablism. Riccardo Balli had now transformed into DJ Balli, ready to move back to Italy and introduce the global underground to his unique brand of breakcore “alla Bolognese”.

However, when the genre landed in Italy, a country whose sprawling and intense illegal rave scene intertwined with its counterculture and its radical left, it largely stayed a one-man affair. Balli soon began bringing all of his DBD friends to the Link Project. Then, in the early 2000s, he started hosting regular breakcore parties at the Vicolo Bolognetti cultural centre in the San Vitale district of Bologna. For a very long time tho, he remained the only true champion of the genre in the whole country. Soon enough he too would launch a label of his own: Sonic Belligeranza, which served as a manifesto for his own vision of what breakcore could become — essentially, anything. Transcending its more rave-oriented roots and embracing the situationist idea of playful cultural rioting, Balli used breakcore as a vehicle to experiment, deconstruct, and subvert bits of popular culture, turning them into ugly, unsettling tools of mass deprogramming. By approaching each new project with the same radicalism, he helped transform the genre into something both sonically elusive and conceptually hard to define. His vision, while somewhat distinct, also complements Scud’s, creating a cacophony that is not only musical but cultural.

Several generations later, and possibly due to the influence of Balli’s new approach, breakcore has become almost unrecognizable to the older heads. It has passed through the eclectic IDM-like contaminations brought in the early 2000s by artists like Venetian Snares, Kid 606, and Bong-Ra, absorbed the dank influence of meme culture and internet-based trash music, and culminated in a current revival infused with hyperpop elements and manga-inspired aesthetics on one side, and benzo-laden ambient doomerism on the other. Those who know how to identify it, however, know that countless artists and genres are still under the influence of primordial breakcore, or at least present a strong affinity with its Spirit. Very often in scenes far removed from the mainstays of European dance music. After all, as one Praxis newsletter put it, breakcore “could be anything that’s not laid back, mind-numbing or otherwise reflecting, celebrating or complementing the status quo.”

Both DJ Scud and DJ Balli will be featured at the upcoming HYPERLOCAL Festival, hosted by ZERO, where they’ll participate as musical guests and lead a discussion on the history, politics, and cultural impact of breakcore.