La discussione in corso sull’uso del trattino come segno grammaticale impiegato per indicare una persona appartenente a più di un contesto etnico o nazionale, sta diventando sempre più rilevante negli studi culturali. La storia vede la comparsa del trattino in questo contesto tra persone sfollate e rese apolidi, in aree del mondo colonizzate dagli europei (del nord-ovest), come strumento linguistico usato per definire una discendenza e tenere traccia dei legami ancestrali perduti – per lo più a causa di centinaia di anni di cancellazione culturale e spossessamento. Di recente il termine è stato reintrodotto in diverse circostanze, riferendosi a guerre neocoloniali e movimenti migratori, portando a una vasta adozione in molte lingue e con una gamma di usi e significati parecchio ampia.

A causa degli sradicamenti continui, il trattino solleva domande necessarie su assimilazione e integrazione, dal momento che rende più evidenti le complicazioni legali che conferiscono il “diritto” alla cittadinanza e così via. Il trattino traccia percorsi, segna le politiche e le leggi migratorie e, in molti contesti, mette in evidenza le tattiche di alterità e alienazione. Come si definisce l’identità nazionale o etnica in tali condizioni? E, se si sceglie di considerarle, quali sono le implicazioni per la propria vita?

Il termine Afro-Greeks diventa presto un “terreno comune” su cui connettersi, riunirsi, creare e rendersi visibili per tutto un gruppo di giovani di seconda e terza generazione della diaspora africana, per lo più di origine ghanese e nigeriana, che costituiscono la maggior parte della popolazione nella zona.

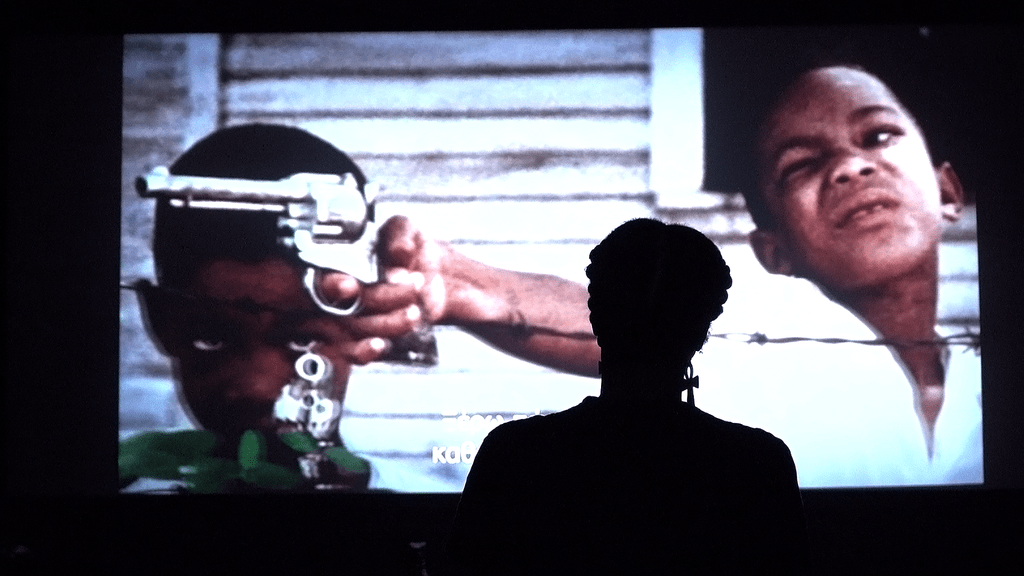

A seconda di di come si utilizza, il tratto d’unione può però anche rappresentare una forma di autoproclamazione dei lignaggi o dell’origine etnica, onorando discendenze e connettendo tra loro i membri delle comunità. Vale a dire, crea solidarietà linguistiche, riconoscendo storie di esclusione e memorie: un gesto di resistenza. È così che ha funzionato l’iniziativa the AfroGreeks, fin dai suoi esordi all’inizio degli anni Dieci, nel bel mezzo dell’ascesa dei movimenti nazionalisti di estrema destra in Grecia. Similmente ad altri paesi dell’Europa meridionale, e profondamente immersa nella crisi finanziaria, la Grecia ha visto l’ascesa di gruppi populisti e neonazisti – molti dei quali con diversi seggi in parlamento – che hanno improntato un’agenda xenofoba volta ad assegnare le responsabilità delle problematiche nazionali, in corso da decenni, alla crisi migratoria. Tale propaganda ha velocemente alimentato e normalizzato violenze e pogrom razzisti contro le comunità migranti ad Atene, e quartieri residenziali come Kypseli e Agios Panteleimonas, dove gran parte degli abitanti proviene da contesti diasporici, sono stati particolarmente bersagliati.

In quegli anni camminavo regolarmente lungo Viale Patission, che divide i due quartieri. Ho assistito personalmente all’aumento della violenza e del controllo poliziesco nei pressi delle due principali istituzioni accademiche della zona – l’Università di Economia e Commercio di Atene, dove studiavo in quel periodo, e la Facoltà di Architettura del Politecnico di Atene: controlli continui basati su profili razziali e perquisizioni fisiche, il tutto accompagnato da trattamenti intimidatori e umilianti. In breve tempo, il razzismo mediatico assieme alla progressiva ghettizzazione dei due quartieri hanno portato a un’ulteriore segregazione dei loro abitanti. In questo ambiente ostile, l’iniziativa comunitaria dei the AfroGreeks va considerata alla stregua di un seme piantato dai greci di origine africana, nati e cresciuti in questi quartieri che, assieme al collettivo Døcumatism – “un gruppo di cineasti, artisti, curatori, storici, lavoratori sociali, ricercatori ed educatori che dal 2009, partendo dall’immagine in movimento e dal documentario, hanno organizzato azioni artistiche e dialoghi pubblici su questioni sociali critiche” – già di sede a Kypseli, si mossero per abbattere le barriere della segregazione. D’altronde Døcumatism era già impegnato nel trovare modi di esplorare e far emergere paesaggi sociali meno evidenti. e in questo senso, Menelaos Karamaghiolis, socio fondatore, ha un ruolo cruciale nella creazione e nel mantenimento di questi sforzi.

Il termine Afro-greco (Afro-Greeks, Αφρο-’Ελληνας/Αφρο – Ελληνίδα) è entrato nel vocabolario greco nel 2011, pronunciato pubblicamente da Mc Yinka. Divenne presto un termine ombrello, meglio: un “terreno comune” su cui connettersi, riunirsi, creare e rendersi visibili per tutto un gruppo di giovani di seconda e terza generazione della diaspora africana, per lo più di origine ghanese e nigeriana, che costituiscono la maggior parte della popolazione nella zona. Questo “terreno” ha lentamente accumulato vita, come mi ha detto Grace Nwoke, membro dei the AfroGreeks, antropologa e performer, quando l’ho incontrata da Døcumatism, indicando una lavagna con una lista di nomi: negli anni, oltre 200 membri della diaspora africana nel paese si sono uniti al progetto e hanno collaborato o co-creato azioni all’interno del progetto, portando avanti diverse voci e esperienze di Atene, in un costante sforzo di mutuo empowerment.

Allo stesso tempo, diversi artisti di base ad Atene, come il collettivo di danza Roots ma anche Mc Yinka, Negros tou Moria e Demelza, per citarne alcuni, hanno diffuso e condiviso l’esperienza afro-greca dai condomini e dalle piazze di Atene al resto del mondo. Con l’obiettivo di diventare uno spazio di empowerment e autonomia, sono così stati organizzati numerosi concerti in spazi pubblici come piazze e cortili e su tetti di istituzioni culturali e artistiche – un momento particolarmente importante fu durante la giornata mondiale della poesia e della lotta contro la discriminazione razziale, mentre erano ancora in vigore le restrizioni del Covid-19.

Un archivio di autodeterminazione, affermazione e resistenza che mette in luce le vite segnate dal tratto d’unione, e i difetti e i regressi delle istituzioni pubbliche e private greche, che continuano a ostacolare qualsiasi crescita dignitosa.

Ognuna di queste attività è documentata e trasmessa sul sito web di Døcumatism, che conta una vasta collezione di materiale video sulle azioni e il coinvolgimento dei the AfroGreeks a livello globale, tenendo traccia delle questioni che la gioventù afro-diasporica affronta nella città di Atene e in particolare a Kypseli, con le conseguenti preoccupazioni, i dubbi e le criticità. Una delle questioni più sentite e urgenti è infatti quella del quartiere: quando ho parlato con loro della rapida e spietata gentrificazione che ha colpito Kypseli negli ultimi anni, un’inquietudine incombente è emersa in alcuni di noi. Come in molte altre città del mondo, quella che inizialmente era stata etichettata come ghettizzazione si è rivelata essere uno strumento strategico nelle mani del mercato immobiliare. A partire dai prezzi scontati di quello che, originariamente, era uno dei quartieri della classe alta della Atene del XIX e XX secolo, è seguito un notevole spostamento dell’interesse degli investitori che ha trasformato rapidamente Kypseli in una delle aree più richieste della città, minacciando così sfratti per famiglie a basso reddito – e spesso di origine migrante –, la cui vita dipende fortemente dal tessuto sociale della comunità circostante.

Il lavoro di Grace Nwoke (AfroGreeks), Menelaos Karamaghiolis (Døcumatism) e di molti altri membri della comunità di the AfroGreeks è dunque cruciale. Un archivio di autodeterminazione, affermazione e resistenza che mette in luce le vite segnate dal tratto d’unione, e i difetti e i regressi delle istituzioni pubbliche e private greche, che continuano a ostacolare qualsiasi crescita dignitosa – personale o professionale – in un’economia già devastata dalla crisi finanziaria, dall’overturismo e dal cambiamento climatico.

The ongoing discussion around the use of hyphenation as a descriptive term for someone belonging to more than one ethnic or national background is becoming increasingly prominent amongst scholars of social studies. Most likely, it first appeared amongst people in parts of the world that have been colonised and displaced by (Northwestern) Europeans, as a linguistic tool to define a lineage, to keep track of lost links of ancestry, mostly due to hundreds of years of erasure and dispossession. Lately, the term has been reintroduced in different contexts referring to neo-colonial wars and migratory movements, leading up to wide adoption in multiple languages, with a wide range of uses and meanings

Due to the ongoing displacement and uprooting caused by Europe’s colonial projects, the hyphen raises essential questions about assimilation and integration. It brings to light the legal complexities that determine one’s “right” to citizenship, and consequently, the right to housing, voting, healthcare, education, and more. The hyphen traces migration routes, reflects on migration policies and laws, and often, in various contexts, highlights tactics of othering. What is the true definition of national or ethnic identity under such conditions? And if one adheres to these definitions, what are the implications for their life?

Depending on its uses, the hyphenation can also be a self-proclamation of people’s lineage or ethnic background that aims to honour the ancestry and connect members of communities with each other. It creates linguistic solidarities, acknowledges histories or erasure and honours remembrance as a gesture of resistance. This is how the AfroGreeks initiative has functioned, from its beginnings in 2015 (while actions were already taking place from 2009), amidst the rise of the extreme right nationalist movements in Greece. Similar to the other Southern European countries and immersed deeply in its financial crisis, Greece faced the rise of populist and neo-nazi extremist groups, many of them with several seats in the parliament, who built a xenophobic agenda to blame the refugee crisis for the country’s internal problems that have been accumulating over decades. The rapidly accelerating propaganda enabled a sequence of violence and racist pogroms against migrant communities in Athens and elsewhere, normalised by governments and media. Certain residential neighbourhoods of Athens, such as Kypseli and Agios Panteleimonas, were the most targeted ones since a big part of their inhabitants were of diasporic background.

These were also the years when I was regularly walking across the Patission Avenue that divides the two neighbourhoods. For years, I bore witness to the increased police violence and monitoring around the two main academic institutions in the area, the Athens University of Economics and Business where I was studying at the time and the Architecture Faculty of the Polytechnic School of Athens, whose primary task was to carry out racially profiled controls of passerby’s documents and physical checks accompanied by intimidating and humiliating treatments. Combined with the media’s diffusion of bias, the ghettoisation of the two neighbourhoods led to a further segregation of its inhabitants.

Amidst this hostile environment, the community-driven initiative of the AfroGreeks came as a seed planted by several Greeks of African descent who were born and raised in those districts. Together with the collective Døcumatism, “a group of filmmakers, artists, curators, historians, social workers, researchers, and educators, who since 2009, starting from the moving image and documentary, have been organising artistic actions and public dialogues on critical social issues” who already housed an art studio in Kypseli at that time, they came together to break the barriers of segregation. Døcumatism was already busy “exploring invisible and inaccessible landscapes […], initiating dialogues to find possible solutions to crucial social issues,” as they state in their description. Their founding member, Menelaos Karamaghiolis, played a crucial role in creating and sustaining these efforts.

The term Afro-Greek (Afro-Greeks, Αφρο-’Ελληνας/Αφρο – Ελληνίδα) entered the Gree vocabulary in 2011 when mentioned publicly by Mc Yinka. It became the crucial umbrella or better, the “shared ground”, for a group of second and third-generation youth of the African Diaspora mostly of Ghanaian and Nigerian origin that consist of the majority of the population in the area, to connect, gather, and create. But also to be seen. That “shared ground” slowly accumulated life as the AfroGreeks member, anthropologist and performer, Grace Nwoke told me when I met her at Døcumatism, pointing at a blackboard with a list of names: throughout the years, 200+ members of the African Diaspora in the country have joined the project and collaborated in or co-created actions within the project, bringing forth different voices and lived experiences living in Athens, in a constant effort of mutual empowerment.

And so, the long-overdue mics finally reached them—on stages, in panels, and on the streets—through a wide range of activities, from academic symposiums to international exhibitions, dance battles, festivals, forums, and all kinds of public cultural events. At the same time, several of these Athens-based artists, such as the dance collective Roots, but also Mc Yinka, Negros tou Moria and Demelza, to name a few, have, in their ways, disseminated and shared the Afro-Greek experience from the flats and squares of Athens to the world. Aiming at becoming a space for empowerment and agency, the initiative, together with artists-members of the community, has organised numerous concerts in public spaces, such as the ones in Athenian squares and institutional yards and rooftops during the global day of poetry and elimination of racial discrimination while the Covid19 restrictions were still in place. Accessibility to such events is equally important for some members of the local communities who might face financial and social constraints.

All these activities are documented and streamed on the website of Døcumatism , a vast collection of moving image material that illustrates the actions and involvement of the AfroGreeks worldwide thus expressing their concerns, doubts and criticalities towards the current issues that the Afro Diasporic youth faces in the city of Athens and more particularly in Kypseli. The future of their neighbourhood is one of the most pressing issues. When I spoke to them about the rapid and ruthless gentrification affecting Kypseli in the past years, a looming worry came to some of us. As in many other cities of the world, what was initially framed as ghettoization of Kypseli served as a strategic instrumentalisation on behalf of the real estate market that managed to lower significantly the prices of one of the formerly upper-class districts in 19th and 20th century Athens. What followed was a substantial shift of investor interest, quickly transforming Kypseli into one of the most requested areas of the city, while threatening with evictions families of low incomes and often with migrant backgrounds, whose life highly depends on the social fabric of the surrounding community.

The crucial work of Grace Nwoke, Menelaos Karamaghiolis and many other members of the evergrowing community of the AfroGreeks is ongoing and building an archive of affirmation and resistance that will belong to these communities. By exposing different layers of hyphenated lives, it exposes the flaws and throwbacks of Greek public and private institutions that keep impeding any dignified – personal or professional – growth in an economy already ravaged by the financial crisis, over-touristification, and climate crisis.